Making the Case for Case Studies

Posted April 4, 2018

By Amber Chenoweth

The Dilemma

Professor Andrews has been struggling to find a way to engage her students in ways to be scientifically literate and be aware of pseudoscience. All she gets are blank stares from her students when she brings up the topic! “How can I engage them in thoughtful discussion and help them see the relevance in their daily lives?” she thought to herself.

Finding a Solution

Professor Andrews approaches a colleague, Professor Smith, with her dilemma. Professor Smith suggests that she consider using a case study.

“A case study? How would that work? And where would I find the time to create one? My class is tomorrow!” laments Professor Andrews.

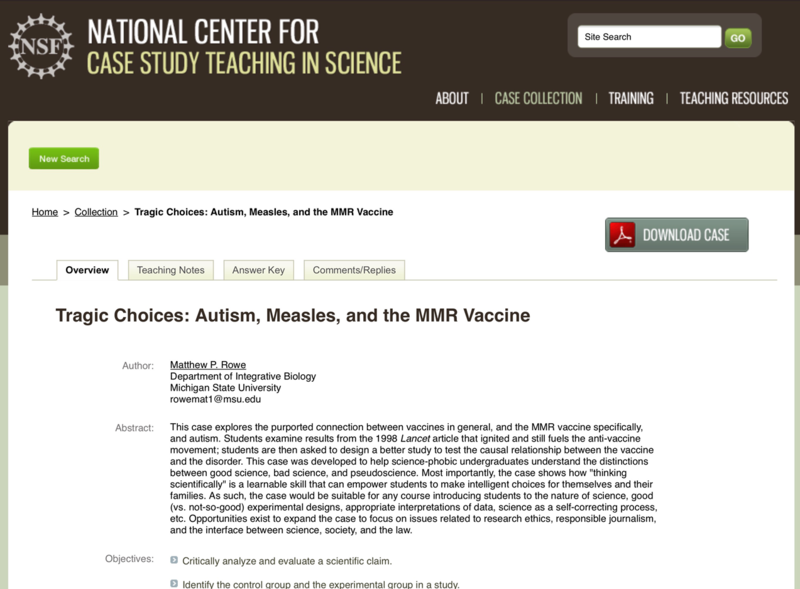

“There are a lot of great resources out there for case studies. Many are already peer reviewed, classroom tested, and ready for you to use,” replies Professor Smith. “Go to the website for the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science. They have over 700 peer reviewed case studies, complete with materials to help you use them effectively in the classroom.”

“But aren’t those for courses in Biology?” inquires Professor Andrews. “Where am I going to find something appropriate for my Intro Psychology course?”

“While a good number of their cases are developed by instructors in and geared towards the ‘hard sciences,’ they have cases written for and can be translatable across many disciplines. I've found several that work wonderfully in my Psychology courses,” replies Professor Smith. “Look – this one will work for the exact topic you’re wanting!” Professor Smith shows Professor Andrews a case study called Tragic Choices: Autism, Measles, and the MMR Vaccine.

“Perfect! And the teaching notes look helpful, too!” exclaims Professor Andrews.

The following week Professor Smith and Professor Andrews talk about her experience using the case study in class.

“It was great! The students were engaged in the material and with each other. The class discussion was so much richer – the case stimulated more creative thinking, and they wanted to learn more.” says Professor Andrews. “They’re already asking about when we’ll use another one in class!”

Reality or Wishful Thinking?

You may be asking yourself, “Does this seriously work?” I get it. It sounds too good to be true and seems like a way to get out of lecturing. But we need to get away from only lecturing! The literature is clear: when students are engaged in the learning process, they develop better critical thinking skills, and retain concepts for a longer period of time (Krain, 2010). Case studies are just one of a multitude of ways to achieve this level of engagement, and I would argue one of the easiest to implement.

I have used case studies as a part of my own pedagogy in the last three to four years, having stumbled upon a case study website in pursuit of Open Education Resources for another project. My initial interest in using case studies was further strengthened by attending a weekend conference in 2015 hosted by the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science (NCCSTS) based in SUNY Buffalo. There I learned best practices for using case studies in the classroom, and attended a session on how to write my own case studies. Overall, the take-home message was clear: case studies can be used in a variety of courses to engage students in special topics and strengthen understanding of existing concepts.

As an example, one of the topics I like to explore with my students in my Biopsychology course is on the distinction between sex and gender, particularly as awareness of transgender issues has become more prevalent on my and other college campuses. I like to use the case Nature or Nurture: The Case of the Boy Who Became a Girl, which presents the real life story of David Reimer who was born Bruce, but after a botched circumcision was gender reassigned as Brenda and raised as a girl. The Biopsychology text I use talks about the same animal research evidence discussed as part of the case study, but presenting this case as a story where students can explore additional aspects beyond the science – the clear ethical questions, and deeper discussion about gender identity – makes for a richer experience and understanding.

I also like to use Tragic Choices: Autism, Measles, and the MMR Vaccine mentioned in the vignette above in an interdisciplinary course I team teach with a theatre colleague, exploring Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) through performance. A goal of this course is to gain an understanding of the science of ASD, which includes students critically thinking about the evidence presented about causes of and treatments for ASD. In addition to looking at the scientific evidence supported, we can expand the discussion to explore how social influence perpetuates pseudoscience.

As a final example, I enjoy using the case Joe Joins the Circus (or Elephant Love): A Case Study in Learning Theory when covering the concepts of classical and operant conditioning in Introductory Psychology, and can push students beyond the case when used in my Learning course. This case guides students to think critically about the types of conditioning used, as well as applying the learning principles to the characters in the case. This application component is key to increasing student retention of the concepts. The NCCSTS case study search feature on their website is also quite helpful in finding cases to address specific concepts, methods, and even level of education to best meet your student outcomes. When I first started looking for cases to illustrate learning principles for my Introductory and Learning courses that led to finding Joe Joins the Circus, for example, I did a simple keyword search for “learning theory,” and it was among the top results.

The Positives

As noted in my experiences above, there are many positives to using case studies in the classroom. First, the story-telling format is engaging and relatable. Many of the students get into the story, and for some I even have them act it out and become the characters.

Case studies lend themselves to small group work. In my observations, I have found that this allows for more opportunities for participation, particularly from my quieter students. By discussing their thoughts to the question prompts in the case in a smaller group, I can see that they are engaged, even if they opt to not be the group spokesperson when it comes time to share as a larger group.

I have also observed in my own students a desire to go beyond the questions in the initial case prompts. Students want to find meaning and application for the concepts covered in courses, and to understand why and how something happens. Often times this pushes me to extend my own thinking on the topic, and I can model how I approach and grapple with critically thinking through these ideas. This translates into allowing a more in-depth experience with a topic that might only get superficial coverage in a text, as I noted above in my example of exploring sex and gender in my Biopsychology course.

Be Prepared

While the case study approach, in my experience, is overwhelmingly positive, there are things that instructors need to be aware of when adopting case studies into their pedagogy.

First, classroom time management is key. Cases can often take longer than you may anticipate. One feature as part of the cases found on the NCCSTS website are that they include an approximate time frame. However, to allow for learning differences in the classroom, as well as extended discussion on topics, I try to allot some buffer time. One tip that has also come in handy is to hold firm to time limits. Set a timer for students to work on a given section of the case and hold them to it. For longer cases, or ones that draw upon supplemental literature, you can also make use of a flipped format, asking students to complete readings outside of class and come prepared to apply the concepts to the case to be discussed in class.

Second, and this will come as no surprise to even the most inexperienced instructor, students + small group work = off-topic chit-chat. While this may seem inevitable, there are some ways to mitigate. One method I often employ is to assign the small groups so students are less likely to end up in a group of just their immediate friends in the class. Another method, regardless of group assignment, is to be present in the room, walking around, checking in on understanding, and holding them accountable as they do their small group work. This can also provide impromptu opportunities to identify concepts that multiple groups may be struggling with and taking a class “time out” to clarify issues, or to offer encouragement as they discuss their responses to the case prompts. This has the added benefit of giving you some ideas for students to call on when you come back together as a group.

Additional Recommendations

Use the case study beyond the classroom session. In my experience, students are more engaged with the case if it is used beyond the single classroom session. I often make “call back” references to case studies in later class sessions, or ask them to incorporate what they learned from applying concepts in the case to later quizzes, exams, or other assessment opportunities. For example, I will have students do follow-up assignments with the cases, challenging them to expand upon the key points covered in the case and incorporating additional literature.

Modify cases to fit your needs. The cases available through NCCSTS have been developed by instructors to meet the needs for their own courses, but their specific learning outcomes may not match yours. The NCCSTS actually encourages instructors to modify cases to fit their needs, and even provides instructions. I have done this for cases where I may want to have students focus on the psychological concepts of a case that may include more advanced biological concepts.

Can’t find a case that fully meets your needs? Create your own case studies. Or even have your students create cases. I have personally found developing my own cases as fun opportunities to engage in creative writing that can be fulfilling in ways that scientific publication does not always allow. You can also share your cases with the teaching community through an easy submission format to NCCSTS. They also have workshop and other training opportunities for you to learn about how to use case studies in the classroom as well as how to develop your own case studies.

Conclusion

The following semester Professors Andrews and Smith are talking over coffee.

“I’m so glad you suggested using case studies last semester,” exclaims Professor Andrews. I’ve added more cases to my Intro Psych course this semester and the students are more engaged and even scored better on their first exam compared to last semester.”

“That’s wonderful! What topics have you done? I’m always looking for more ideas,” replies Professor Smith.

“I found a great one for learning theory, and cases on eyewitness memory and psychological disorders. I also found a great case to use in the social psychology unit that looks at unintentional racism, and another I use in the development unit that examines autism.”

Professor Andrews found many cases to meet the needs of her class. What topics in your course could you enhance with a case study?

Author note: This blog post was adapted from a presentation delivered by Dr. Chenoweth at the Society for the Teaching of Psychology Annual Conference on Teaching in San Antonio, TX, October 2017.

Author Bio

Dr. Amber M. Chenoweth is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Psychology, and Honors Program Director at Hiram College (Hiram, OH). She recently completed a Mellon Fellowship to develop with a team of her colleagues Hiram’s Connect initiative to engage students in reflective and integrative learning. Dr. Chenoweth teaches courses on the psychobiology of behavior, introductory and career preparation courses in the psychology major, and team-taught interdisciplinary courses, ranging in topics from autism spectrum disorder to study abroad courses in Australia and Zambia. She is passionate about teaching, advising, faculty development, and using technology creatively in the classroom.