The Ancient Impulse: A Brief History of Play and Games

Posted August 20, 2015

By Tom Heinzen

@heinzent

This is Part 2 in a series on the value of games in education and learning. Part 1 is HERE.

It’s not easy to find humor related to suicide but Epictetus came close. The first century (C.E.) stoic Greek philosopher observed, “…just as [children] say, when the game no longer amuses them, ‘I will play no more,’ you too, when things seem that way to you, you should say likewise, ‘I won’t play any longer, and so depart. But,” he added (with a hint of a smile?), “if you stay, stop moaning” (see Hard, 1995, p. 53).

But moaning about going hungry is probably exactly what the people under King Lytus of Lydia, in Asia Minor, were doing, according to Rawlinson’s (1861) translation of The Histories of Herodotus. In this case King Lytus attempted to help his people survive a terrible famine by alternating days of game playing with days of eating.

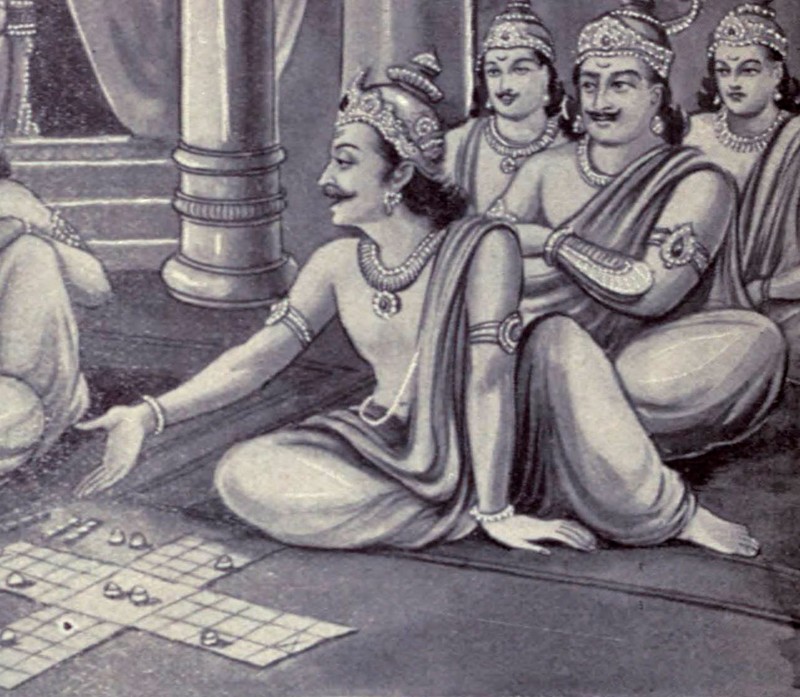

The ancient Greeks were not the only ones to find meaning in games. Another ancient but more treacherous example comes from the Hindu myth of Shakuni, pictured below, who won with fixed dice what he could not win by war.

As you can see, game-playing is ancient and seems to have exerted remarkable powers that have been credited both for evil and for good.

We can look to the recent past (in this case, 1798) to understand why games are associated with evil. Madame Stael de Holstein (pp. 155-163) lumped together “the passions of gaming, avarice, and drunkenness” as causes of the French revolution. She seemed vaguely aware that the correlation between widespread gambling and the frequency of heads being lopped off was not necessarily causal. But in light of the bloodletting, she wanted to encourage in citizens a “philosophical apathy when they can think without enthusiasm.” Her grim motto could have been, “Better depression than death.” In 1832, John Parkhurst reached a similar conclusion when he argued that governments should not sanction gaming (gambling) because, “If a thing is evil in itself, to give it the sanction of law only increases the evil.” And in 1838, Jeremiah Day (1838) dragged god into the conversation by asking, “why one [person] prefers to go to the gaming table, while another goes to the house of prayer.” One obvious answer did not seem to occur to Jeremiah Day: playing is more fun than praying.

What is it about playing with chance that inspires interpretations that range from mass murder to knowing the mind of God? Games are just a set of rules, so games are amoral. Immorality comes from those who get to write those rules, pass the laws, fix the dice, or take advantage of others’ statistical naiveté to bend the laws of chance in their favor. Combe and Fowler (1844) did not seem to need divine inspiration to assert the health benefits and “superiority of cheerful play and amusing games.” In 1894, John Lubbock (62-77) perceived important social benefits to honest games, such as teaching a man “how to get on with other men…to give way in trifles, to play fairly, and push no advantage to an extremity.” So, asking “Are games evil or good?” seems to be the wrong question, no matter how many people claim that god is on their side.

The entertainment industry didn’t need a Nobel laureate, psychological training, or insights from the Prisoner’s Dilemma to hear the sweet sound of money sliding into slot machines or passing into their pockets through games of chance. The golden age of radio in the 1930s and 1940s created huge audiences by using game shows such as Quiz Kids and Truth or Consequences to lure audiences into new patterns of shopping behavior. The 1960’s television version of The Price is Right, pictured here , illustrates how game show designers used classical conditioning to motivate people to buy more butter, soap, and laundry detergent. Just as Madame Stael de Holstein seemed slightly confused about correlation and causation when commenting on the causes of the French revolution, academics may shun using games to motivate students simply because games are so often correlated with superficial entertainments.

The ground has shifted beneath the academic feet of higher education because our students appear to be happily saturated in a game-based, digital world. A 2010 report by the video game industry (with estimated annual revenues of 10.5 billion dollars) tells us that students voluntarily spend about 8 hours per week playing video games and 40% of those gamers are females (who tend to prefer the Wii to the Xbox). About 49% of gamers are between 18 and 49 years old and about 64% of parents believe that games are a positive influence on their children; 48% of those parents play video or computer games with their children about once per week. And that’s only the video game industry. It doesn’t count people who volunteer to coach softball, play tennis, attend a weekly poker game, or periodically donate their money to slot machines (http://www.esrb.org/about/images/vidGames04.png) .

To paraphrase John Lennon, history is what happens to you while you are planning something else. Games are not beneath higher education; games have moved past higher education and it’s time for us to catch up. The stoic philosopher Epictetus had it right. If you’re going to play, stop moaning about unmotivated, underprepared students. If you’re going to stay, then play!

So, if you want to discover how game-based principles can induce extraordinary levels of persistence in students previously labeled as “unmotivated” and “under-prepared,” then watch this space….

Note: Follow the link HERE for an extensive bibliography of game-related references.

Bio

Tom Heinzen is a professor at William Paterson University, works in game design for higher education, has authored with Susan Nolan a statistics textbook, and is an interdisciplinary methods geek He has published peer-reviewed articles as experiments, case studies, quasi-experiments, focus groups, surveys, theoretical models, novels about teaching psychology, several book chapters, academic books, a history about Clever Hans and facilitated communication, and even edited a book of poetry by nursing home residents. Game design is especially appealing because it is a natural home for interdisciplinary applications.