Active Learning, Blah, Blah, Blah: The True Confessions of a Dangerously Active Teacher!

Posted October 6, 2015

By Aaron S. Richmond

It is your first day of teaching introductory psychology. Young faces with blank stares are looking down at you from afar. Your heart is pounding. Sweat starts to bead on your forehead like rain on a windshield. Your palms begin to moisten as if you were in a confessional booth purging all your sins. These visceral reactions are because you have come to realization that you are largely responsible for their first impression and knowledge of psychology. What do you do? How do you engage your students for 75 minutes?

I just modeled active learning. I brought you in (cognitively activated you), related this blog to your personal life, and engaged you. Now I will try to explain some of my confessions (they are confessions because they are hard lessons I’ve learned) about using active learning instruction.

Confesión Numero Uno!

I am not here to tout one instructional method over another. In fact, research on exemplary teachers suggests that they use varied instructional strategies to engage their students—one of which is active learning instruction. Active learning is generally thought of as instruction that engages students by having them experience concepts (active behavior) or requires learners to think about concepts (active cognition). The good news is that there is a plethora of resources available for you to become an active and engaged teacher (see the must read section below).

Moral: Develop active learning instruction as an arrow in your quiver of instructional strategies.

La Confession Deuxième: Show Me the Money/Evidence!

As alluded to, active learning has been widely studied in the field of psychology. If you search the journal Teaching of Psychology for “active learning” you will find over 700 results. So what does all this research tell us? Answer: When used properly, active learning increases academic performance. Specifically, there is a growing body of research that suggests that it is particularly advantageous for increasing higher-level learning. Active learning also increases student’s perceptions of teaching effectiveness (otherwise known as student’s ratings of instruction; SRIs). Although, SRIs are not the end-all-to-be-all, they are widely used for merit and promotion in academia.

Moral: Active learning may increase your student’s academic performance and your SRIs.

What it Takes to be an Active Learning Teacher

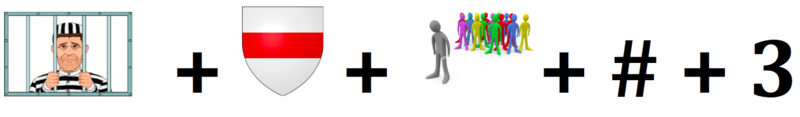

First and foremost, research suggests that effective active learning activates student’s cognition more than their behavior (e.g., what is the answer to the rebus?). For instance, when teaching intelligence theory, I give my students the Black Intelligence Test for Cultural Homogeneity (yes, the BITCH Test). Students always perform poorly—tantamount to mental retardation according to a normal curve. Merely giving them the BITCH test would only activate their behavior, but this is not enough. Rather, I must actively and cognitively probe their experience, how the activity relates to IQ tests, what role does culture have in IQ theory, what does this mean to them personally, what does this mean from a theoretical standpoint, etc.

Moral: Make sure you reflect, debrief, engage in metacognitive practices, and connect content to student’s prior knowledge and beliefs.

Second, well-executed active learning requires a willingness to fail on your part. I have tried so many different activities, demonstrations, varied class discussions, technological gadgets (my current fav is ©CELLY to text my students), or whatever it took to engage students. NOT ALL OF THEM WERE SUCCESSFUL! Yes, you have to be willing to fail, but you don’t know if you failed unless you assessed the efficacy of the method.

Moral: Always assess the implementation of introducing an active learning method.

Finally, effective active learning requires time, effort, and commitment on your behalf. In essence, teachers who use active learning—do their homework! They research different active methods by reading articles in Teaching of Psychology, Psychology Learning and Teaching, or Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology. Additionally, they commit to preparing good activities as opposed to winging it! For instance, whether using cooperative learning activities (see Morling et al., 2008 for use of iClickers), or a think-pair-share (see Hakala, 2015 NOBA blog), or a classroom demonstration on auditory perception (see Haws & Oppy, 2002), all of these instructional methods took time to learn, refine, and master.

Moral: Be a student of the game!

The IV confession: Snake and Charlatan Avoidance

Developing active learning methods can be fun, exciting, and challenging, but with “great power, comes great responsibility!” That is, we need to consider the potential harmful effects that some active learning methods can have on individual students.

For instance, I often use a great (insert #egocentric here) demonstration on action potential by asking students to line-up, put their right hand on the person’s shoulder in front of them, then squeeze the person’s shoulder, then the last student at the end of the axon shoots a water gun at another neuron (see Felsten, 1998 for complete description of the activity). What if students didn’t feel comfortable with touching others or shooting something or felt coerced into participating? How would they feel? Will the demonstration be counterproductive to learning? If the answer is yes, to any of these questions, then something needs change.

Moral: Always ask students to volunteer to participate in activities and do not penalize them for not volunteering.

Another problem stems from the notion that many students are skeptical of some classroom experiences, especially those that re-create classic experiments. They feel like they are being set up to fail. For example, to demonstrate the effects of deeper processing in long-term memory, I divide students into two groups: one gets a shallow processing strategy (e.g., counts the number of e’s in a word) while the other gets a deeper processing strategy (e.g., free associate with the word). Both groups then map their performance on the board in histograms. Inevitably the students who have the deeper strategy significantly outperform the other students. If not properly implemented, half my students may feel dumb, embarrassed, or even humiliated.

Moral: Be honest and forthright about what will happen, give opportunities for students to do something else, and provide opportunities for anonymity to avoid being a charlatan.

The Confessio:

In the end, we have all experienced the beads of sweat (either real or imagined) caused by the understanding of how important our job is as psychology teachers. However, being an engaged teacher through the effective use of active learning techniques will promote your students attention, their enjoyment with your class, their respect and trust for you, and will invariably increase their knowledge of psychology.

A Must-Read Before You Hit The Proverbial Pillow!

If you are interested in reading more and acquiring specific examples for introductory psychology courses or beyond, please check out these outstanding resources.

Afful, S. E., Good, J. J., Keeley, J., Leder, S., & Stiegler-Balfour, J. J. (2013). Introductory Psychology teaching primer: A guide for new teachers of Psych 101. Retrieved from the Society for the Teaching of Psychology web site: http://teachpsych.org/ebooks/intro2013/index.php

Felsten, G. (1998). Propagation of action potentials: An active participation exercise. Teaching of Psychology, 25, 109-111.

Griggs, R. A., & Jackson, S. L. (2011). Teaching introductory psychology: Tips from ToP. Retrieved from the Society for the Teaching of Psychology Web site: http://teachpsych.org/ebooks/tips2011/index.php

Hakala, C. (2015, March 4th). Large classes??? How do I deal with that? Retrieved from http://nobaproject.com/blog/2015-03-04-large-classes-how-do-i-deal-with-that

Haws, L. & Oppy, B. J. (2002). Classroom demonstrations of auditory perception. Teaching of Psychology, 29, 147-150.

Morling, B., McAuliffe, M., Cohen, L., & DiLorenzo, T. M. (2008). Efficacy of personal response systems (“clickers”) in large, introductory psychology classes. Teaching of Psychology, 35, 45-50.

Miller, R. L., Balcetis. E., Burns, S. R., Daniel, D. B., Saville, B. K., & Woody, W. D. (2011). Promoting student engagement (Vol 2): Activities exercises and demonstrations for psychology courses. Retrieved from the Society for the Teaching of Psychology Web site: http://teachpsych.org/ebooks/pse2011/index.php

Richmond, A. S., & Kindelberger Hagan, L. (2011). Promoting higher level thinking in psychology: Is active learning the answer? Teaching of Psychology, 38(2), 102-105. doi: 10.1177/0098628311401581

Segrist, D. (2008). I’d like to use active learning…But what can I do? The Observer, 21(11),Retrieved from http://www.psychologicalscience.org/index.php/publications/observer/2008/december-08/idliketouseactivelearningbutwhatcanido.html

Silberman, M. (1996). Active learning: 101 strategies to teach any subject. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

I know the stress of anticipation is killing you. Thus, the Rebus solution: Con + fess (it’s a real word) + shun + # + 3 = confession number three. And yes, I stole this great idea from my friend Dan Segrist, checkout his article on active learning.

Bio

Aaron Richmond received his Ph.D. Educational Psychology from the University of Nevada, Reno. He is a national award winning teacher, the Vice President for Programming for the Society of Teaching of Psychology, an editorial board member of Teaching of Psychology, and has published extensively on the scholarship of teaching and learning.