Jumpstart Your Teaching with the Jumpstart Lesson Planning Model

Posted April 20, 2016

By Lynne N. Kennette

We know that each of our students learns in different ways, and have a preferred way of receiving and interacting with information to learn it. Because of this, it can be a challenge for instructors to ensure that we meet each of their needs. We also know that students have an ever decreasing attention span, so lecturing for an hour (or even 15 minutes!) is not ideal. When preparing to provide learning opportunities for our students in class, it is sometimes difficult to keep all of these things in mind while planning lessons (especially since we have a preferred way of learning/teaching as well!) Struggle no more! Use the Jumpstart model for your lesson-planning and you WILL be able to address the many types of learners in your classroom (and make teaching/learning more fun and active in the process).

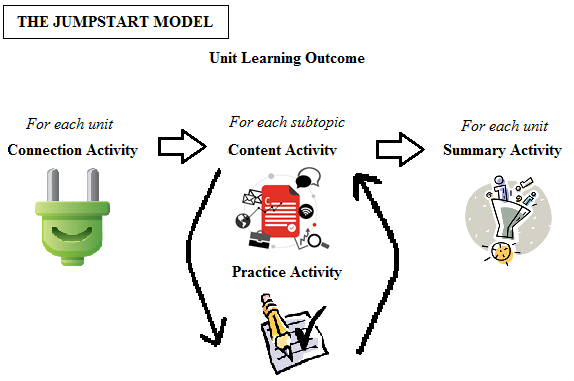

The Jumpstart Lesson-Planning Model

At Durham College (Oshawa, Ontario, Canada), we use the Jumpstart model for lesson planning, which captures students’ attention, chunks content into short lessons, and enables students to manipulate or practice the material immediately after each chunk. This helps instructors to structure their lessons to include multiple ways for students to receive, interact, and practice the material.

The Jumpstart model contains 4 different types of components: connection activity, content activity, practice activity, and summary activity.

To begin each unit (this can be a chapter, topic, learning outcome, or class period), you first engage students by connecting what they already know to the material that will be covered. This makes the link between the content and the student’s real life (or future work life) and answers the question “why should I learn this?” This can take the form of an image, case study, discussion, video clip, newspaper article, poll, etc.

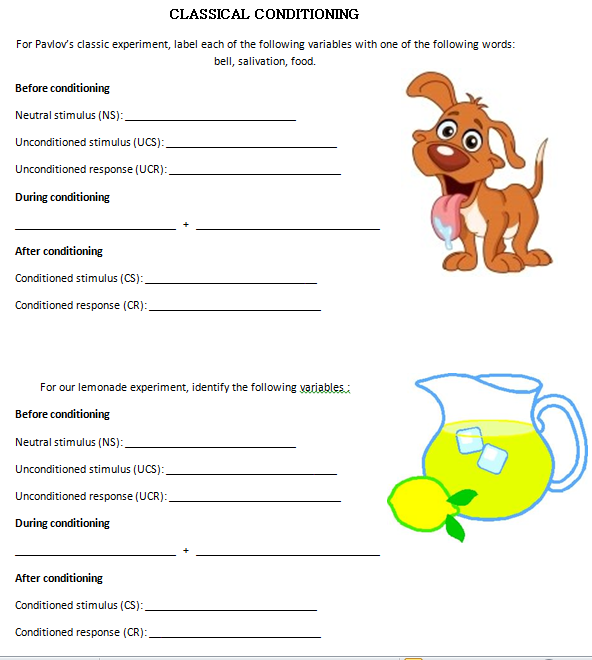

Then, for each topic within your unit, you present small chunks of information (Content activity) followed by the opportunity to practice that content (Practice activity). The Content activity provides students with the information (i.e., what they need to know) and the practice activity allows them to practice this new knowledge or skill to let students gauge whether they have mastered the content being taught. Here are some examples:

- show a video clip (e.g., nervous system) and have students create a concept map

- have students engage in an experiment or watch your demonstration of a phenomena, then complete a worksheet

- present information using a brief traditional lecture, then ask students to self-test (you can create fun assessments using Hot Potatoes (dowloadable for free from https://hotpot.uvic.ca/) or purchasing IF-AT scratch cards from Epstein (http://www.epsteineducation.com/home/))

- ask students to present information on a topic to their classmates (e.g., defining features of a disorder), then ask the class to practice identifying disorders using case studies

This content-practice cycle is repeated (and varied) for each topic within the unit.

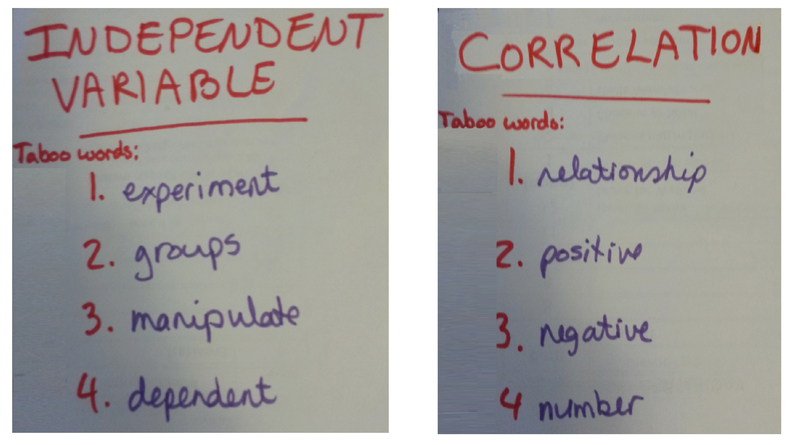

At the end of the unit, a Summary activity provides students with the opportunity for synthesis and metacognition, reflecting on their mastery of the unit content and figuring out how all of the pieces fit together. For example, students can create test questions (or review games/activities such as Taboo-style cards) in a small group or summarize the unit in one sentence, or write down what is still unclear about this unit (muddiest point).

Theoretical Foundations of the Jumpstart Model

Durham College’s Centre for Academic and Faculty Enrichment (C.A.F.E.) developed the Jumpstart unit planning model to organize lesson plans to appeal to each learning style and provide students with active learning experiences (this project was headed by Ruth Rodgers, now retired, based on her previous work at the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology). The Jumpstart model is loosely based on Kolb’s idea of learning styles, and also fits with more recent neuroscience work by Zull. Both of these are briefly described below.

Kolb proposed that each person has a preferred style of learning as part of his experiential learning theory (Kolb & Kolb, 2005). Some people learn best by doing, others by feeling, others by watching, and others still by thinking. His four learning styles assign learners to one of these learning styles: Diverger, Assimilator, Converger, and Accommodator.

- Divergers need to be convinced to learn the material, so they benefit from the Connection activity in the Jumpstart model.

- Assimilators just want to be given the information that must be learned, so they prefer the Content activities

- Convergers want to try it for themselves, so the Practice activities are most valuable to them.

- Accommodators want to explore this new knowledge with peers and so the Summary activity is their preferred learning style.

Zull’s research has expanded our understanding of the physical, neurological changes that occur as a result of learning. He proposes that learning occurs by using 4 different regions of the cortex:

- sensory cortex (get information through experience)

- temporal integrative cortex (make meaning through reflection and observation)

- frontal integrative cortex (generate new ideas and hypotheses)

- motor cortex (act on these new ideas by actively testing them).

Thus, his proposal is to engage the whole brain during the course of learning, which the Jumpstart model allows you to do with minimal effort.

Zull (2004) proposes that learning (i.e., changes in the brain) requires practice and the experience of emotions. When students solve a difficult problem, for example, the reward chemicals that are released result in a feeling of intrinsic motivation for them. Practice is especially important because it results in physical changes in the brain (Draganski, Gaser, Busch, Shcuierer, Bogdahn, & May, 2004). Draganski’s team demonstrated this by having novices practice juggling. After practicing and achieving mastery, these jugglers showed increased density in some areas of the brain; this increased density was reversed when they stopped practicing to juggle, which resulted in a reduction in their juggling skills.

So, Jumpstart gives your students the opportunity to use their whole brain during your class and ensures that at some point, your unit lesson will appeal to each student, regardless of their preferred Kolb learning style. Zull (2004) summarizes the benefits of varied learning opportunities: “If teachers provide experiences and assignments that engage all four areas of the cortex, they can expect deeper learning than if they engage fewer regions. The more brain area we use, the more neurons fire and the more neural networks change and thus the more learning occurs.”

My Experience

Having used this lesson planning model for the last 4 years, I can honestly say that it has made planning lessons easier and helps me to include more variety (activities). I find it an easier way to organize my thoughts and plan my lessons. Typically, I work backwards from the LOs, then plug in the activities/demos/experiments, and then fill in the gaps. Specifically, this model ensures that you’re always thinking about how students can practice what you’re teaching them, which is an area that many forget to include (I know I was sometimes guilty of this prior to joining Durham College and using the Jumpstart model).

As with any teaching technique, it’s not fool-proof. If you plan to use the Jumpstart model, I would suggest that you try it with one class/lesson (one that you want to improve right now anyway!) and work from there. Additionally, ensure that your lessons include a variety of tools to deliver the material, practice, etc. If you’re still lecturing for the majority of class time, you’re not using this to its fullest potential. One vastly under-utilized resource in the classroom is other students. Our students’ networks look different than ours, so it can be more difficult for us to present course content at their level; sometimes using peers to deliver the content can be beneficial to bridge that gap (Bowman, Frame, & Kennette, 2013; Zull, 2004).

Finally, take some risks. It may not always work out exactly as you had planned (e.g., technological issues), but I think students would rather see you try something new and fail (fully or partially) than bore them with traditional lectures for 3 hours/week.

Bio:

Lynne N. Kennette received her Ph.D. in Cognitive Psychology (Psycholinguistics) from Wayne State University (Detroit, Michigan). She is a professor of psychology and program coordinator (General Arts and Science program) in the School of Interdisciplinary Studies at Durham College (Oshawa, ON, Canada). She has won numerous teaching awards, including two from the Society for the Teaching of Psychology. She is passionate about psychology, teaching, and learning.

References

Bowman, M., Frame, D. L., & Kennette, L. N. (2013). Enhancing Teaching andLearning: How Cognitive Research Can Help. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching: Brain-Based Learning (Special Issue),24(3),7-28.

C.A.F.E. (2012). The Jumpstart unit planning model. Centre for Academic and Faculty Enrichment, Durham College. Retrieved from http://cafe.durhamcollege.ca/index.php/teaching-learning/the-jumpstart-model

Draganski, B., Gaser, C., Busch, V., Schuierer, G., Bogdahn, U., & May, A. (2004). Neuroplasticity: Changes in grey matter induced by training. Nature, 427, 311-312.

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2005). Learning Styles and Learning Spaces: Enhancing Experiential Learning in Higher Education. Academy Of Management Learning & Education, 4(2), 193-212. doi:10.5465/AMLE.2005.17268566

Merriam, S. B., & Brockett, R. G. (2011). The profession and practice of adult education: An introduction. San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Zull, J. E. (2004). The art of changing the brain, Educational Leadership, 62(1), 68-72. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/ASCD/pdf/journals/ed_lead/el200409_zull.pdf