Use it or lose it: Why and how to provide opportunities for your students to practice course content

Posted April 27, 2017

By Lynne N. Kennette, Lisa R. Van Havermaet, and Bibia R. Redd

We give our students a lot of information over the course of our weekly hours with them, but how often do we give students an opportunity to interact with, apply, or otherwise practice the course content? Not allowing enough opportunity to practice can pose a problem when we later ask students to use this content in some way (e.g., on an assignment). The Jumpstart lesson planning model used at Durham College ensures that lectures are broken up (or chunked) with opportunities for students to practice (with “practice activities”) in between presentations of new content (C.A.F.E., 2012). A previous NOBA post (Kennette, 2016) described the Jumpstart lesson planning model in detail, so you can read that first if you’re interested. This post will first briefly discuss why it is important to allow students to practice course content, then provide examples of tools and techniques to allow students to practice content, and finally, share some tips for success.

Why should students practice course content?

Practice activities allow students to engage with the material in a more concrete way and to practice the skills or knowledge they were exposed to in a particular unit of a course. Research has shown that there are many benefits for learning when students practice what they are learning, including neurological evidence of changes in the brain (e.g., Draganski, Gaser, Busch, Schuierer, Bogdahn, & May,2004; Zull, 2004). And, by allowing students to practice their newly-learned knowledge, they can also get a better sense of how they are doing in the course and whether they are actually understanding the material. That is, are they developing their metacognition, which is a powerful indicator of learning (Wang, Haertel, & Walberg, 1990).

One key feature of any practice activity is that it allows students to retrieve the information that was just presented in the course. Retrieval practice is well-established in the literature as improving outcomes (e.g., long-term retention). For example, Roediger and Karpicke (2006) compared students who had studied the same material four times to students who had studied it once and then were tested on the material three times (so both groups had 4 sessions with the material, the first of which was always a study session). Results showed that, although immediate performance was comparable across the two groups, the students who were tested three times (and therefore retrieved the information multiple times) significantly out-performed the study-only group both two- and seven-days later.

The bottom line is that the features of many types of practice activities are well established in the literature as providing benefits for learning: retrieval (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006), metacognition (Wang et al, 1990), immediate feedback (Dihoff, Brosvic, Epstein & Cook, 2004), collaboration (Rajaram. & Pereira-Pasarin, 2007), etc.

How to practice

The benefits of providing practice opportunities are clear, but finding suitable exercises and activities isn’t always easy. With that in mind, we’d like to provide you with a number of ideas that we have successfully used to help students practice, either in class or outside of class. Because, even if you use this approach of giving students opportunities to practice course content; you may still run out of ideas or resources to provide these opportunities to practice. Below are some examples and resources to use for practice activities including games, tests, and concept maps.

Games

Using games is the easiest both for student buy-in and because they are generally fun due to the inherent features of games (e.g., competition, prizes/winners, etc). Some popular examples include Taboo, Headbandz/Heads-Up, Jeopardy, Pictionary, etc. In each case, the practice activity can be to generate the game (e.g., to create a Taboo card for a concept covered) or to play the game (with instructor-generated materials), or both (have groups of students create the games and then a different group will play it)!

Self-Tests

and create html tasks for students to practice (crossword puzzles, fill-in-the-blank, etc).

Concept Maps

Concept maps are another way for students to practice, synthesize, and organize the information presented in class. Here, students organize information in meaningful ways (e.g., hierarchically, or grouping in some way) and make links among the concepts. Online resources include Cmaps, Bubbl.us, and MindMeister. Many other opportunities exist as well for students to practice course content. These include case studies, debates,creating infographics or word clouds to summarize material, think-pair-share, more traditional worksheets, etc.

Planning for success

Now that you have some ideas, how should you begin incorporating opportunities to practice in your classroom? Before you begin, remember that the goal is for students to practice (perfection is not the goal at this point!), so students should get feedback (but NOT grades) on their performance on these practice activities. This feedback can take the form of faculty, peer, or self-marking, or the feedback received could be built into the outcome of a hands-on application (e.g., Did the program you coded actually work?). By ensuring that the activities are low/no-stakes, they will encourage students to take risks with their learning and truly practice the content.

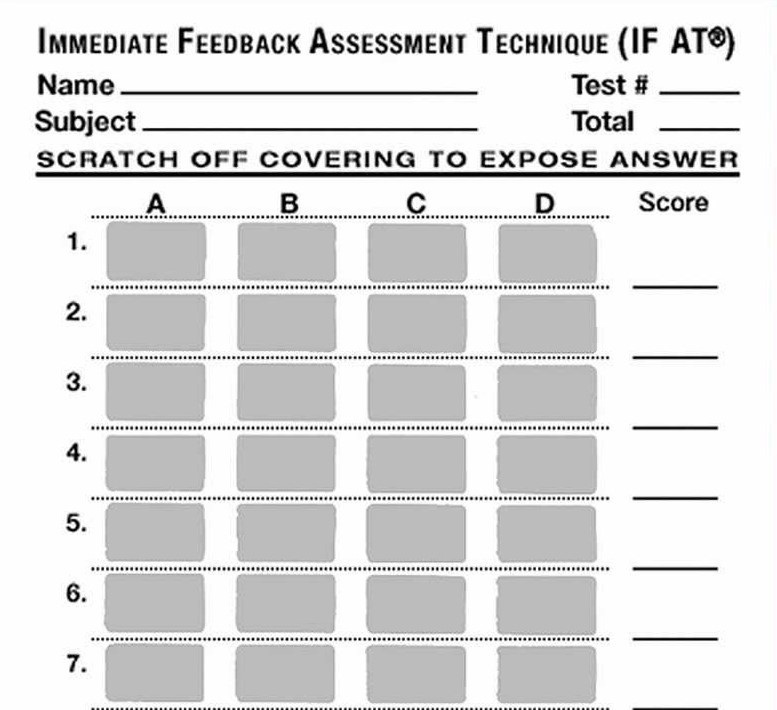

Another point to keep in mind is that in some courses and topics, the practice comes more naturally. For example, in a statistics course, you teach a lesson, and the students practice via assigned problems. In other content areas, it will take more effort to develop opportunities for students to practice. For example, when teaching about the history of psychology, it’s not intuitive to have students practice that content, however it is still important. Although practice is important, don’t go overboard or you will exhaust both yourself and your students! Yes, it is important for students to practice the content, but start small, perhaps by developing something to give students the opportunity to practice one particularly difficult concept in the class. Or, consider using the same technique (e.g., IFAT scratch cards) as a weekly feature of the course so that students become accustomed to it.

Also, some of the activities described here may not work for your students. If you have a class filled with general education students, you’ll need to use a different approach for your practice activities than if you have a class of upper-level majors. Finally, you also need to find a balance between the amount of information presented in class and the amount of time spent on practice; too much of either would not be ideal. Typically, you will probably spend about 10-15 minutes providing the content, and then 5-10 minutes on a practice activity, though this may vary somewhat based on the specific topic covered. Regardless, the underlying premise is the same: students need to practice the content they are encountering. After all, if they don’t use it, they’ll lose it!

Bios

Lynne N. Kennette received her Ph.D. in Cognitive Psychology (Psycholinguistics) from Wayne State University (Detroit, Michigan). She is a professor of psychology and program coordinator (General Arts and Science) in the School of Interdisciplinary Studies at Durham College (Oshawa, ON, Canada). She has won numerous teaching awards, including two from the Society for the Teaching of Psychology. She is passionate about psychology, teaching, and learning.

Lisa R. Van Havermaet is currently a professor of Psychology at Clarke University (Dubuque, IA). She received her Ph.D. in Cognitive Psychology from Wayne State University (Detroit, MI). Her interests include psycholinguistics, embodied cognition, and pedagogical methods.

Bibia R. Redd received her Ph.D. in Social-Development Psychology from Wayne State University (Detroit, Michigan). She is a Lecturer of psychology in the Department of Psychological Science at University of North Georgia (Gainesville Campus). She is the mother of two daughters, and one granddaughter and believes the transfer of knowledge to be one of the greatest legacies anyone can leave.