Stimulating Curiosity Using Hooks

Posted June 7, 2017

By Kentina Smith

Our Biggest Rival for Student Attention

What are students doing in the back of your classroom?

If you’ve taught a class in the past decade you’ve no doubt experienced the infamous long eye-glaze or students’ constant glances to their laps and casual slumping behind a strategically placed purse or backpack. All of this in an effort to conceal something deemed a higher priority or more appealing than course content for the day – cell phone use.

There’s no getting around the fact that cell phone use is an integral part of our students’ daily activity. But cell phone use, unrelated to active class participation, can present a challenge in the educational environment and the process of learning. However, it also provides valuable insight into what interests our students and how we can engage them with course content.

Emotional Student Engagement: Curiosity

“Being curious can help us build relationships, allow us to become more engaged, be more personally invested, and possibly most important, curiosity motivates us to learn.” – Sue Abeulsamid

Cell phone and Internet use may seem more enticing to students than the opportunity to learn in a classroom for many reasons. It is interesting and dynamic, offering a variety of ways to interact with information and learn what others’ think, feel, and know about any given topic. But perhaps more importantly for us as instructors, it offers a way for students to satisfy curiosity. If we can engender the same sense of curiosity with course content we’ve got a better chance to compete with our formidable rival.

Stimulating Curiosity Using Hooks

To tap into student interests and curiosity, I use the instructional strategy of “hooks” at the start of each class session. I also use “hooks” in professional development sessions. Hooks are brief lesson content teasers, relevant activities, stories, songs, provocative questions, headlines, current events, images, demonstrations, videos, or case studies designed to stimulate interest, curiosity, and active interaction with information that can be connected to course concepts. The key is to not exceed 10 minutes; 5 minutes is ideal. The hook is not the lesson, it is the intriguing trailer for the lesson.

Being curious is the jumpstart to expanding knowledge, testing out ideas, generating hypotheses, and discovery. Research and classroom experiences suggest that student interest, enjoyment, and perceived value of the content are important factors in the learning process. These factors, along with curiosity, describe emotional engagement in the classroom. Emotional engagement is not a requirement, for student learning but it is worth the investment to create an environment and experience where student input and contributions are encouraged, welcomed and valued.

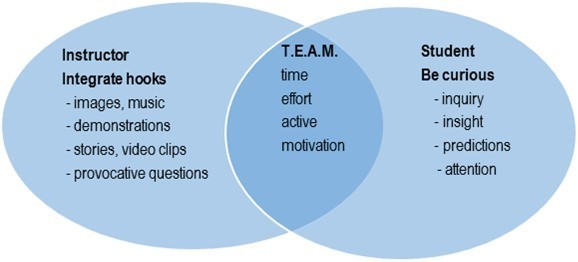

The Venn diagram represents my basic ideal goals, when integrating hooks in my classroom.

Hooks can demonstrate:

- misconceptions about the discipline

- student experiences and interests relevant to connecting course content

- that content can be applied in a variety of ways

- the importance of being good consumers of information

- that diverse thoughts and experiences, and being contributive partners in the learning process is important to awareness of differences

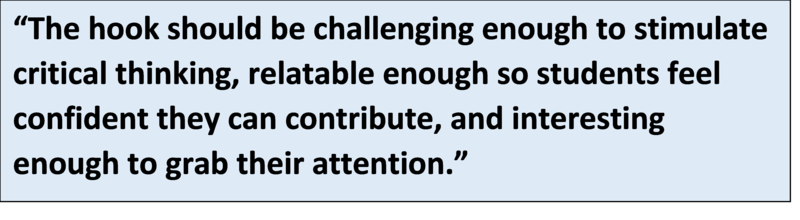

Starting a lesson with an engaging hook is one way to introduce or review concepts students tend to perceive as dull or difficult. Intrigue and accessibility are key components of a good hook. The hook should be challenging enough to stimulate critical thinking, relatable enough so students feel confident they can contribute, and interesting enough to grab their attention.

An ideal hook allows all students to be actively engaged, even the ones in the back of the classroom. To further stimulate curiosity, I do the following:

a) graciously thank all students for active participation, but avoid giving any specific feedback

b) move on to the lecture introducing new terms, and instruct students to think about how their responses and experiences from the hook connect to specific terms throughout lecture.

During hooks, when students publicly share information – accurate and inaccurate – my strategy is to thank them for contributions and sort out facts from misconceptions later during lecture. During hooks, I respond with general statements like “very interesting”, “hold that thought, it’s going to be really important to help explain key concepts”, “stay tuned” or “we shall see”.

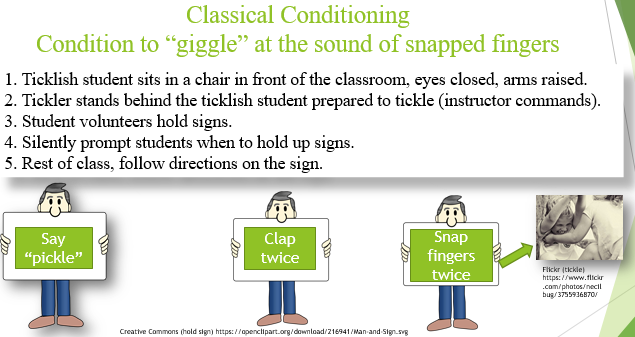

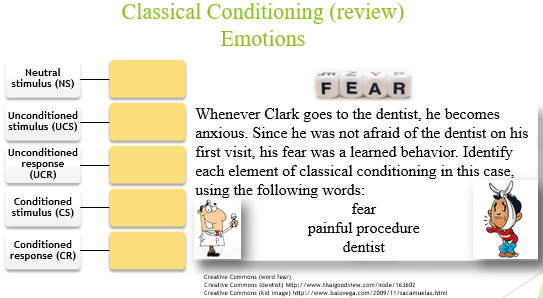

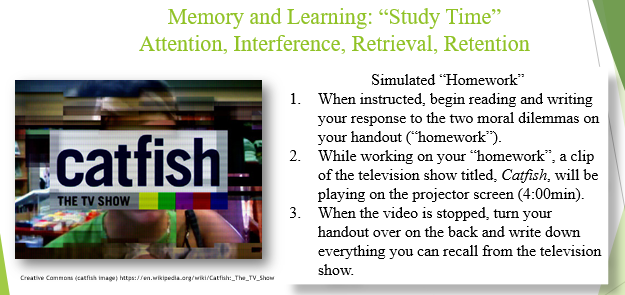

Here are a number of example hooks used in my classroom.

In my courses, students tend to prefer video clips of popular television shows or movies to connect to course concepts. There are a wealth of videos online. Amazon also offers free trailers online. At times, creating and locating hooks that connect with both students and content takes quite a bit of time and effort. However, some can be as simple as one intriguing question, a moral dilemma, professional scenarios, an image, or snapshot you took to share with students. For a comprehensive list of movies, along with their descriptions and ratings, content covered, discussion questions, and activities, check out the website called Teach with Movies, found at http://www.teachwithmovies.org/

Some hooks will work well with one class but not another class. I find out as much as I can about all of my students so I can value who they are and what they bring by using relatable hooks. Each student completes an online form, to provide me with the following information: major area of study, interests, and why the course can be important in life, career, or personal academic pursuits. Students and engagement matters.

Bottom line: Curious students tend to be engaged; invest in hooks.

Bio

Dr. Kentina Smith is an assistant professor of Psychology at Anne Arundel Community College. Her area of scholarship is educational psychology. She has been in the field of education for more than 20 years and holds an advanced professional certification in teaching. Her experience has involved working with toddlers, managing literacy programming, inclusion classroom co-teaching, mentoring teachers, working with adolescents’ social and emotional skills and teaching in middle schools and college.

For further information, contact the author at Anne Arundel Community College at 101 College Parkway, Arnold, Maryland 21012. Email: [email protected]

References

Abeulsamid, S. (2016). That’s a really good question: Start the curiosity revolution. Retrieved from http://www.thatsareallygoodquestion.com/

Carter, A. E., Carter, G., Boschen, M., AlShwaimi, E., & George, R. (2014). Pathways of fear and anxiety in dentistry: A review. World Journal of Clinical Cases : WJCC, 2(11), 642–653. http://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i11.642

Linnenbrink, E. A., & Pintrich, P. R. (2003). The role of self-efficacy beliefs in student engagement and learning in the classroom. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 19(2), 119–137. doi:10.1080/10573560308223

Mintz, S. (n.d.). Transformational teaching. In Science of learning: The psychology of learning and the art of teaching. Columbia University: Graduate School of Arts & Sciences Teaching Center. Retrieved from http://www.columbia.edu/cu/tat/pdfs/psych_learning.pdf

Smith, K. (2015). Student engagement: Getting 21st century students hooked into your instruction. Innovation Abstract, 37(26). National Institute for Staff and Organizational Development: University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved from https://www.nisod.org/password/online_abstracts/archives/pdf_archives/XXXVII_26.pdf

Trowler, V. (2010). Student Engagement Literature Review. York: Higher Education Academy. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu/743769/Student_engagement_literature_review