Turning Students Into Scholars by Reducing Resistance to Learning

Posted August 8, 2018

By Anton Tolman & Trevor Morris

Anton Tolman: I remember a moment, several semesters ago, in my Abnormal Psychology course. We were exploring diagnostic issues related to personality disorders. A student raised his hand and asked a relevant question. I paused, and because I wanted the class to apply the integrative biopsychosocial model we had been using all semester, I returned fire with a follow-up question, pushing them to think about the issues involved. In response, one student got an incredulous look on her face and with a come on, really? voice said out loud, “Why can’t you just answer the question?”

I was surprised by this reaction. This was a normally good student overtly pushing back against my pedagogical approach. However, instances like this are not unique to my classes. “Student resistance” happens all the time, in all kinds of classes, whether we recognize it as resistance or not, and it is especially common in courses that emphasize active learning.

. . .

Why is this important? As John Tagg in the forward to our book Why Students Resist Learning (Tolman & Kremling, 2016) wrote so well:

The irony is blatant and really quite agonizing if we dwell on it. What works to get students to learn, to learn resiliently, to learn what they can use and when to use it, is something students do not naturally like nor are necessarily drawn to. They fight what is good for them. We have the cure for what ails them, but they resist the treatment. (Tagg, 2016, p.ix).

The implications of resistance are far-reaching. When students resist course activities and assignments or put in minimal effort, they are not learning content nor are they building critical skills. Worse yet, they see resistance as necessary, a response to external demands instead of recognizing their own responsibility to learn. In a very real sense, student resistance threatens the purpose of education and its value to a civil society. The good news is that by understanding its sources, we can proactively address them, reduce resistance in our classes, improve learning, and enhance the joy of teaching. We’ll share some ideas of how to assess and intervene to lower student resistance.

I Don’t Have Resistance in My Classes…..or Do I?

We would argue that it is fairly easy for faculty to not recognize resistance when it happens, for a variety of reasons. One of these is that the teaching literature has not really addressed this issue head on. Most of the time resistance is mentioned or described with lists of proposed reasons why students are behaving this way but lacking a coherent definition. So, we decided to propose one:

Student resistance is an outcome, a motivational state in which students reject learning opportunities due to systemic factors (Tolman & Kremling, 2016, p.3).

This definition is useful because it describes resistance as the outcome of interactive systemic factors -- in other words, it can be understood; it results from known, inter-dependent factors that can be assessed and for which interventions can be planned.

Trevor Morris: I think I develop good rapport with my students. Their feedback is generally positive. I work to reduce resistance by explaining to them the rationale for the pedagogical methods I choose. As a result, I would classify resistance in my classes as low.

However, student resistance can arise at any time even for faculty who do not often see it. For example, I had been using Eric Mazur’s peer instruction technique for three semesters. Students used clickers to respond to a question and then discussed it before answering again. Early on in the new semester, I explained the technique and how it has an impact on learning. But after a couple of class periods a student insisted that she couldn’t use the clicker because it caused her too much stress. Not only that, she had recruited another student to her position! I tried again to explain my reasons for using this particular technique, but to no avail. They insisted that I make accommodations for them because they wouldn’t be using clickers.

. . .

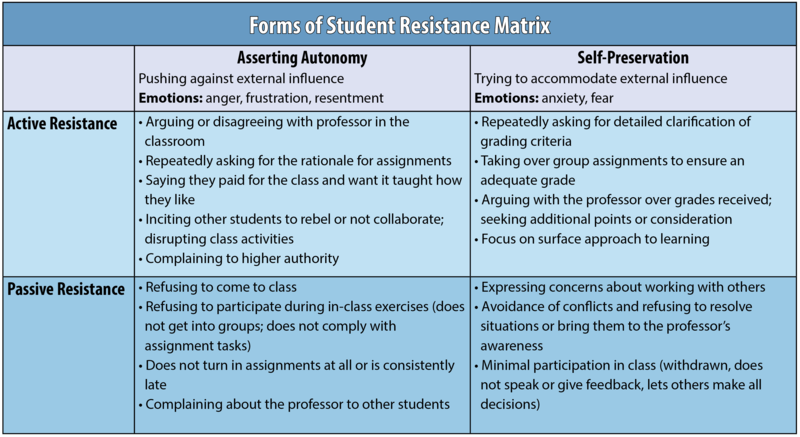

Trevor’s example illustrates active student resistance, but resistance can come in many different forms, not all of them easily identified. Instructors are likely to dismiss active resistance as due to ego, perfectionism, entitlement, or other internal explanations. But as psychologists, we should recognize this as the Fundamental Attribution Error (FAE). To get past this common human foible and understand the deeper reasons for resistance requires a conceptual framework – an alternative way to understand and explain what is happening. Take a look at the Student Resistance Matrix.

We believe that resistance stems largely from two motivational sources: students are trying to protect themselves, to “get through” the class without taking too much damage, or to get grades to secure their future goals; alternatively, they may be “pushing back” against the teacher or a system that they believe is trying to force them to change who they are, or to adopt a set of ideas or a worldview they disagree with. This can include student perceptions of negative elements of societal power that often are embedded in our institutions or in our own thinking such as sexism, racism, and other -isms. Resistance can also take active or passive forms.

While our two examples in this essay are active, it is even easier to dismiss passive resistance as student laziness or lack of interest. However, this should set off our FAE red-alert lights again. The situation is more complex than these easy-to-jump-to conclusions. The Student Resistance Matrix is the first step forward – it helps us recognize when resistance is occurring. It tells us that student resistance occurs for a reason – it has a purpose and a goal. It is a communication SIGNAL. Students are telling us something by these behaviors, and once we realize that, we can begin to figure out what is happening and how to reduce resistance to open up student motivation to learn rather than to resist.

Systemic Forces

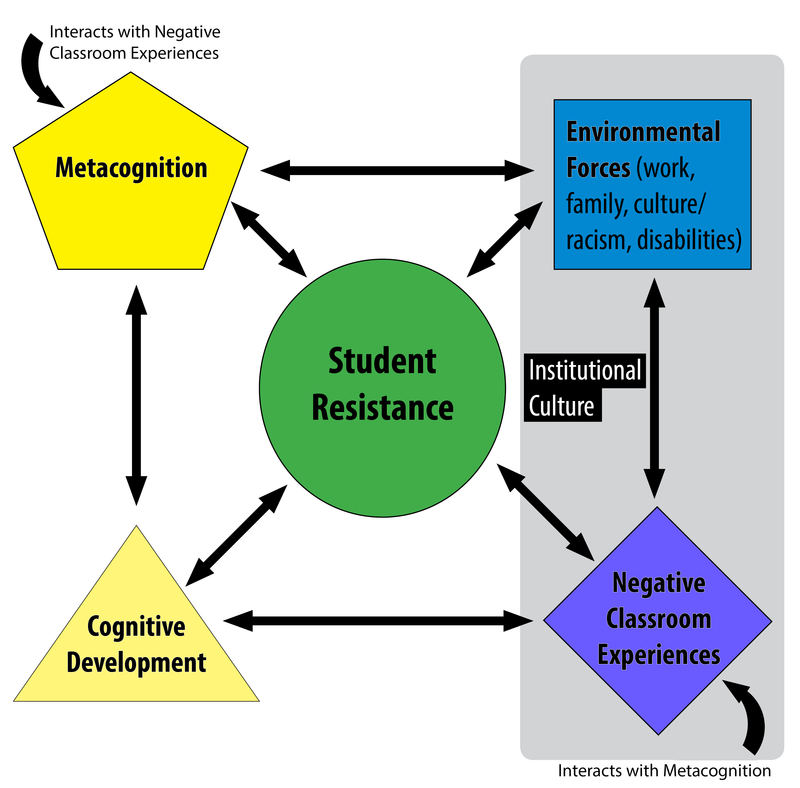

As noted in the definition of student resistance, these behaviors are the outcome, the result, of interactive systemic forces. Looking broadly across the pedagogical literature, we identified five systemic factors that usually interact to produce student resistance, each making their own contribution. We call this the Integrated Model of Student Resistance (IMSR):

As you can see in the graphic above, the IMSR consists of five interacting elements. We will skip the “institutional culture” element which shapes and influences both environmental forces and educational experiences because we want to focus primarily on interactions in the classroom. Here is a brief description with an example of the other four elements of the model. As you read these, consider how these forces would interact as well as shape both passive and active forms of student resistance in class.

1. Social and Environmental Forces: These include many different aspects of familial and social forces that shape student expectations about education, influence their thinking about the amount of effort that is “reasonable” to use in learning, and that contribute to student stress and sense of alienation in our classrooms.

Example: Imagine a first-generation or immigrant student who is struggling to feel comfortable on campus; then a family member becomes ill, and she believes her primary moral obligation is to help her family rather than to study or turn in homework.

2. Negative Prior Experiences: Students do not come to our classes as blank slates. They bring with them their own histories of previous educational encounters with institutions and teachers; unfortunately, for many students these previous interactions have been negative and shape what students expect of their teachers and influence how they interpret and react to instructor behaviors. In our book (Tolman & Kremling, 2016), there are also stories of how instructor misbehaviors and lack of interpersonal attention and warmth towards students also has significant negative impact on student expectations and motivation to learn. Even though you may believe you are supportive and careful in your teaching, your students may bring with them the wounds of these prior experiences.

Example: In the book, a student describes a history of painful interactions in elementary and middle schools (including being told she had a “dumb math brain”) that convinced her that she was academically incompetent and unable to succeed; it took her years and many experiences to convince herself that she was capable of success and to enter higher education. Imagine such a student in a class with an instructor who, for good reasons, is encouraging students to stretch beyond their comfort zones and to take risks.

3. Cognitive Development: Multiple scholars have documented the developmental paths in adult cognition that shape how students see the world around themselves and their view of the purpose and goals of education. At lower levels of development, students tend to be very concrete and believe that the goal of education is to learn “the right facts” and tend to be focused less on skill development and critical thinking and mostly on memorization and acquisition of factual knowledge. Students can make progress and develop, but it can take time as well as scaffolded and supportive experiences for this to happen.

Example: Imagine a student who believes the instructor’s role is mostly to convey and describe important facts and concepts in a field being asked to work in collaborative projects with other students he views as being as ignorant as himself; he is likely to view the teacher as abdicating their proper role to teach.

4. Metacognition, or the Lack of It: Many students come to our classes with little awareness of study strategies or what produces better learning. Hopefully, they learn basic study skills in middle or high school, but many never progress beyond memorization. Even in higher education, students may learn some more effective study strategies, but they often do not transfer these skills to other courses. Thus, if they struggle in classes that are more demanding or that require them use critical thinking skills, they frequently see the problem not as their own fault, but as lack of competence by the instructor.

Example: Imagine a student who mostly succeeds in school by doing exactly what the instructor asks and has honed efficient methods for memorization. She then takes a course requiring analysis of case studies and the use of problem-solving methods to solve complex cases. The exams use applied questions, and she finds herself consistently performing below her own expectations.

In addition to understanding each of the areas of the IMSR, it is helpful to consider how these elements interact. Consider a student entering school with consumerist expectations (learned at home or from others), who is also lower in cognitive development, unaware of his own mastery level with regard to important learning outcomes, and who has a history of being praised for quick memorization of vocabulary and definitions in the past. Now imagine that student entering a course where the rules are different, where collaboration and active participation are required, and where course objectives include demonstration of effective communication and problem-solving skills. Hopefully, the IMSR provides teachers with a lens on these important elements that contribute to resistance. To some degree, each student’s resistance is their own, but it is fairly common that there will be patterns across many students in a course of how these elements interact, depending on the nature of the institution, the schools that provided prior instruction to students, and the demographics and cultural elements of the region.

Getting Started

You’ve probably heard the question, “How do you eat an elephant?” The answer is “One bite at a time”. While we do not advocate consumption of pachyderms, this approach has some merit. Once an instructor begins to understand that resistance, both passive and active, is a signal and not noise, has begun to determine the motives that drive it, and uses the IMSR to determine what is causing it, the next step is to do something about it. The question is where to begin, and the answer is that it will vary with each instructor.

One idea is to begin where you can. It begins with understanding the signal the students are sending – and that signal may be different depending on the instructor, the course itself and where it fits into the major program, the student population, and other factors. Consider the course(s) you are teaching and given what you have determined about the sources of resistance, identify a target for change. This may involve redesign of the course, identifying new objectives, or better aligning assignments and assessments to those objectives or changing assignments to better develop and scaffold new skills; in another class, it might entail beginning the semester by involving students in discussions about the value of the pedagogy and how it will help them achieve their professional and personal goals (see Smith, 2008 for some ideas); another class may involve directly addressing concerns about stereotype threat and working to build support for open discussions from all perspectives, and so forth.

Consider the IMSR as a tool for intervention, not just assessment. Is the largest source of resistance coming from negative experiences students are bringing with them? If so, enhancing your relationship with students, being open and asking for their input and experiences may be very valuable. If it is lack of metacognitive awareness, consider using brief metacognitive tools, reflective assignments, and explicit instruction in how to succeed in class as key pieces to enhance student learning. (See the appendix of Tolman & Kremling, 2016 for some examples).

Learning to effectively and usefully address student resistance is a learning process for the instructor as well as the students. The more practice we gain at seeing resistance and using the IMSR, the more we are able to respond constructively. You don’t have to address all areas of the IMSR at once; resistance is a systemic outcome. This means a couple of important things: the system itself will resist change – systems tend to establish homeostasis and try to remain stable. On the other hand, by intervening at one strategic point, you can begin to influence the whole system; as you gain understanding and experience and have significantly addressed one part of the IMSR, you can shift to another and increase your success. One bite at a time.

We believe that student resistance is one of the major sources of frustration and burn-out for those who teach. The more we learn to reduce our students’ resistance to learning, the more joy and engagement we experience as teachers. We also help students develop into more responsible, actively engaged scholars in our classrooms. They begin to see the value of education more clearly in their lives, and we all improve as learners.

Additional Resources

For those who want to learn more about how to identify and overcome student resistance, the book Why Students Resist Learning is worth investigating. Available from Stylus Press, it can be purchased through the end of 2018 at a 20% discount by using code WSR20.

Bios

Anton Tolman received his degree from the University of Oregon (go Ducks!) and is Professor of Behavioral Science and former Director of the Faculty Center for Teaching Excellence at UVU. His research interests focus on classroom power dynamics, metacognition, and student resistance. He and his wife live at the feet of beautiful Mt. Timpanogos in Utah, and he is a strong advocate for the value of board games in bringing joy to life. Anton can be reached at [email protected]

Trevor Morris received his Master’s degree from Palo Alto University. He has taught as an adjunct faculty member for the Behavioral Science department for over six years. He is a Faculty Development Specialist for the Office of Teaching and Learning at UVU, and he has worked in faculty development for over seven years. Trevor can be reached at [email protected]

References

Smith, G.A. (2008). First day questions for the learner-centered classroom. National Teaching and Learning Forum, 17(5), 1-4.

Tolman, A.O. & Kremling, J. (2016). Why Students Resist Learning: A Practical Model for Understanding and Helping Students. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Tagg, J. (2016). Foreward. In A.O. Tolman & J. Kremling (Eds). Why Students Resist Learning: A Practical Model for Understanding and Helping Students. Sterling, VA: Stylus.