Brave Teaching: Using the Fearless Teaching Framework to Infuse Your Course with Evidence-Based Strategies

Posted July 3, 2019

By Virginia L. Byrne (@virginialbyrne) and Alice E. Donlan (@alicedonlan)

Most faculty want to be excellent teachers. We want to use evidence-based, cutting-edge teaching practices. We want our students to love coming to class and really learn the course content. We want stellar student evaluations. We want to dazzle our department chairs and deans.

But you know what most faculty don’t want to do?

Dedicate lots of time to reading decades of education research.

This is why our Fearless Teaching Framework is a useful tool to help improve college teaching. We distilled decades of research and theory on teaching and learning into set of recommendations for university instructors interested in improving their teaching.

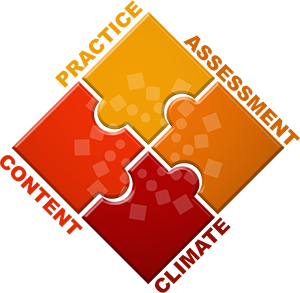

The Fearless Teaching Framework is a conceptual model of the four pieces of effective teaching that promote student engagement and motivation: classroom climate, course content, teaching practices, and assessment strategies (Donlan, Loughlin, Byrne, 2019). Each piece represents aspects of the course that an instructor can control and change as they develop into a better teacher.

We distill our full literature review (Donlan, Loughlin, Byrne, 2019) into these brief suggestions:

Climate – When students feel that the classroom climate is supportive, they are more likely to ask questions, ask for help, support their peers, engage deeply with material, and achieve academically. Instructors have the power to structure the learning environment so that students feel a sense of belonging and that their voices and questions are welcome.

A supportive climate is fostered both in how the instructor establishes the classroom climate at the beginning of the course and how they interact with students throughout the semester. For example:

At the beginning of the semester, the instructor:

- Clearly states that they want students to succeed.

- Positions themselves as a partner in meeting the course objectives.

- Asks for and uses students’ preferred name and pronouns.

- Asks students what they need to learn best – whether it be clearer instructions or closed captioning on course videos.

Throughout the semester:

- When an instance of discrimination, hate, or bias emerge in class or on campus, the instructors is prepared to talk about and address issues that inhibit students from being successful. Learn more about how to handle sensitive topics in class here: tltc.umd.edu/discussions

Content – Students are more successful when the course content is appropriate for their developmental stage and academic ability. Further, students are more likely to be engaged when they understand that the content prepares them for the next courses in their sequence of study, and is relevant to their lives outside of the classroom. In other words, high quality content meets students where they are, and prepares them for where they need to go.

We recommend that instructors:

- Connect course topics to examples from students’ professional and personal interests – including parenthood and community leadership.

- Emphasize how the course content can be used in the real world, for example through Problem Based Learning – meaning that they develop a plan in which students need to apply their knowledge to real-world problems. The application of course content to problem solving helps students retain content and self-assess their mastery.

- Collaborate with colleagues to ensure the learning objectives and content across courses in a major/minor sequence are aligned and build toward mastery.

- Ask students about their prior content knowledge on the first day of class – maybe in an ungraded pre-test survey – to gauge the incoming knowledge of the group.

Practices– When instructors adopt active learning practices and appropriately scaffold new content, students are more engaged with the course material and motivated to learn. We recommend that instructors:

- Rely on strategies beyond lecturing – such as active learning practices. Structuring learning so that students are required to respond to one another’s ideas, create a product together, or teach each other, can be an effective teaching strategy.

- Practice Scaffolding: Instructors can motivate students by scaffolding new ideas to pre-existing knowledge, building a scaffolding system to help them learn and practice new content without going too far, too fast.

- Hold Clear, High, and Reasonable Expectations: By being consistent with praise, corrections, rubrics, and mastery goals, instructors set high expectations that can motivate students to stay engaged. When teachers provide comfort instead of coaching during failure or praise the accomplishment of very simple tasks, it can inadvertently signal that they don’t believe the learner is capable of challenging tasks.

Assessment – We found that learning assessments are most productive when they are valid, reliable measures of stated learning outcomes and provide students with with prompt and fair feedback. However, often too much emphasis falls on designing summative, end-of-semester assessments. We recommend that instructors make time throughout the semester to provide students with formative feedback on their drafts and design clear rubrics that communicate exactly what mastery looks like.

- Provide students with formative feedback mid-way through the semester on a project or paper either through instructor feedback or a peer review process. This process allows the instructor to identify students who need additional support in meeting the course objectives, and allows students to reflect on what aspects of the content they understand and what aspects they need to focus on in future weeks.

- Increase student motivation to study and learn by providing students with a clear rubric. A rubric is a tool that details the gradations of difference between understanding something well and not understanding it at all. Rubrics can require significant effort to construct, but they ultimately decrease the amount of labor dedicated to grading student work by establishing clear expectations.

- Construct assessments with learning objectives in mind and then work backwards to design a rubric and an assessment structure that align with the objectives. Students are more in control of the grade they earn when they can compare their effort and output against a detailed grading rubric and realistic test grades. Rubrics motivate students to work towards the grade they want.

Take-Aways

From our review of the education theory and research literature, we found that instructors can improve their teaching by reflecting on their teaching within the 4 pieces of the Fearless Teaching Framework and setting a goal to change one thing each semester. We are piloting an evaluative instrument based on the Fearless Teaching Framework that we hope to share with the community soon.

Based on the Fearless Teaching Framework and all the recommendations we provided,

What is one thing you will do next semester to improve your teaching?

Want to learn more about the Fearless Teaching Framework? Check out our article at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/tia2.20087

Feel free to contact us to talk more about adopting the Fearless Teaching Framework: [email protected] or [email protected].

Bios

Virginia L. Byrne, M.S., is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Teaching & Learning, Policy, & Leadership at the University of Maryland’s College of Education. Her concentration is in Technology, Learning and Leadership. She serves as the Graduate Assistant for Research and Assessment at the Teaching and Learning Transformation Center. She earned a Master’s in Higher Education: Student Affairs from Florida State University and a Graduate Certificate in Instructional Systems Design from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Learn more about her work at www.virginialbyrne.com

Alice E. Donlan, Ph.D., is the Director of Research at the University of Maryland’s Teaching and Learning Transformation Center. Alice leads the research, evaluation, and assessment efforts at the TLTC, and collaborates with faculty and programs across campus to understand ways to improve teaching and learning outcomes. She earned her Ph.D. in Human Development with a specialization in Educational Psychology and a certificate in Measurement, Statistics, and Evaluation at the University of Maryland.