How to Read Scientific Papers

Posted November 13, 2019

By Noah Jacobson and Robert Biswas-Diener

Fortunately, the blueprint of a psychological research article is relatively universal. With the exception of a few specific types of articles, such as literature reviews and meta analyses, psychology articles consist of five basic sections: an abstract, introduction, methods, results, and conclusion/discussion. Below, I will explain each of these parts. Learning this universal structure lends itself well to clearing up confusion and understanding these technical articles.

Parts of an article

Abstract

The abstract of an article isa simple summary of the entire article. It is usually a single paragraph long and appears right at the beginning, just after the list of article authors. Abstracts generally describe the topic in which the researchers are interested, such as prejudice or the way children learn to read. In just a few sentences, the abstract provides an overview of the study (or studies) that the researchers conducted and a summary of their main findings. Abstracts are helpful in that they contain a snapshot of everything you need to know about the study in order to determine whether you want to read the study in greater depth. This can save valuable time if you are evaluating a number of articles for their potential inclusion in a term paper.

Let’s say, for example, that you want to write a paper on the links between health and happiness. You search several databases for key terms and find dozens of articles on the topic. You cannot, of course, read all of these papers. There simply isn’t time. Instead, you can review abstracts to get a better sense of those that might be the most relevant for your paper. You might be able to exclude, for example, research on children because that is too niche for your paper. You might focus, instead, on those papers that deal specifically with the immune system or those that talk specifically about positive emotions. Abstracts help you preview and organize your approach to curating and synthesizing research.

Introduction

Psychological research papers begin with an introduction. You can think of the introduction as the “why” portion of the paper. That is, the introduction places the current research in the context of past research. This is called a “literature review” and researchers often spend a couple pages describing the findings of previous research and supplying references for these earlier studies. This helps researchers make a case for why their current research is relevant and important. They might argue that their research helps fill in a gap in our existing knowledge, or adds new evidence to support a theory, or helps clear up a confusion created by contradictory results from earlier studies.

Let’s take a look at a specific example. In a 2001 article, researchers Robert Biswas-Diener and Ed Diener investigated the happiness of people living in poverty. That’s pretty straightforward. Even so, they wanted to provide readers with background to better understand the issues related to their study. The introduction to their article includes economic, historical, and social information about Kolkata, India, where they conducted their research. It also contains a brief review of the research literature showing that income is related to happiness and they provide some potential explanations for this relationship. Finally, they make an explicit case for their study by saying that their research extends earlier studies by using a unique sample: people living in dire poverty (Biswas-Diener & Diener, 2001).

The introduction is a great way to learn about the major findings in a field in the span of just a few short pages. It can also be a helpful resource for identifying other articles that might be relevant to your project.

Methods

- Sample. This is a description of the people who participated in the research. Older articles refer to these people as “subjects” and newer ones refer to them as “respondents” or “participants.” The methods sections usually gives a brief description, such as identifying if they are students, or retirees, or people who share a clinical diagnosis. The researchers usually report on the relevant demographic variables related to the sample such as age, gender, educational level, or national or cultural background. There is usually a table of numbers that acts as a visual description of these background variables.

- Measures. Here, you can find a description of the various measures that the researchers used. These can include standard tasks (such as the Stroop Task or the “Uses for a brick” task), questionnaires (such as the “Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale”), or biological measures (such as saliva cortisol samples or genetic markers), or behavioral observations (such as seeing how close strangers versus friends sit to one another). Typically, researchers provide a brief description of their measures, with references to the ways that these measures have been used or validated in the past.

- Procedure. Not all studies include a description of procedures. Experimental studies—those conducted under controlled conditions—often do. This is especially the case if the researchers are using deception or creating an artificial situation. For example, social psychologist Dov Cohen once had a colleague “accidentally” bump research participants as they passed each other in the hall to see how they might react (Cohen, Nisbett, Bowdle, & Schwarz, 1996).

Interestingly, you do not necessarily have to read an entire research article in the order it is written and this is especially true of the methods section. It may be that you simply want to get a broad understanding of the research and reading the introduction and the results is sufficient for your purposes. It may be that you circle back and read the methods section once you have determined that the article is relevant to your interests. If you ultimately include an article for discussion in your term paper, you should definitely read the methods section.

Results

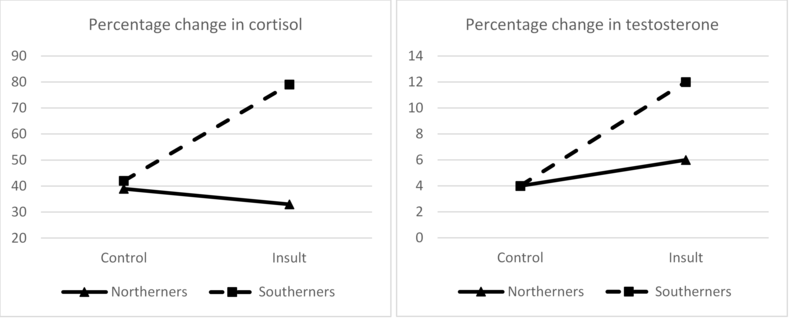

Understanding the results section can be made easier by remembers key sources of information to keep an eye out for: figures and tables. These clear graphics present the numbers in an easy-to-digest and more visually-friendly format. Figures display a relationship between things using an illustration. For example, a figure might show the number of suicides for each age group across multiple years. This is an easy way to see how the suicide rate has changed over time and to identify specific parts of the population (age groups) that have changed the most. Figures can include charts such as bar charts, graphs such as line graphs, and plots such as scatterplots. Tables, by contrast, provide lists of numerical findings in columns or rows. Common types of tables include demographic variables (such as average levels of age or income), the average results of key variables (such as the average self-esteem scores of participants who completed the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale), or correlation matrixes (in which the strength of a relationship between a variable and all other variables is reported).

Discussion

- Summary. Here, the researchers repeat their main findings and discuss them in the context of their original hypothesis or their relationship to earlier research.

- Explanation. Here, researchers occasionally provide some theory to explain their results. Sometimes these are hypothetical and sometimes they emerge from data gathered in the study itself. Researchers also sometimes admit that their study results were contradictory or unexpected. In these cases, they try to advance some explanation of why this might be the case.

- Limitations and further study. Almost all research articles, conclude with the twin pillars of limitations and suggestions for further study. In the limitations portion, researchers identify the strengths of their study but also acknowledge that there are weaknesses as well. They might point to the sample, for instance, as a way of suggesting that their findings are preliminary and will not necessarily generalize to all people. A discussion of the limitations of a study should not be interpreted as invalidating the study. Instead, it is an acknowledgment that science works like a patchwork quilt, with each study providing a simple piece of the overall fabric of knowledge. Researchers typically conclude with a few specific suggestions for further research. If you are interested in a career in research, these statements can be a gold mine of open areas to explore!

In Conclusion

Like any difficult skill, reading psychological science - or any science for that matter - gets easier the more you practice. Learning what is most valuable and what can be passed over saves both time and effort without sacrificing clarity. Once you get the gist of a paper continue on and review the paper in greater depth. Remember, just as an explorer relies on a GPS to find his or her way, you too can rely on the landmarks of any scientific article to keep you on target.

References

Biswas-Diener, R., & Diener, E. (2001). Making the best of a bad situation: Satisfaction in the slums of Calcutta. Social Indicators Research, 55(3), 329-352.

Cohen, D., Nisbett, R. E., Bowdle, B. F., & Schwarz, N. (1996). Insult, aggression, and the southern culture of honor: An" experimental ethnography." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(5), 945-960.

Bios

Noah Jacobson

Noah Jacobson is a psychology and neuroscience major at Grinnell College. He currently works as a research assistant and Peer Educator for Grinnell College’s Department of Wellness and Prevention. He enjoys running, cooking, and spending time in nature.

Robert Biswas-Diener

Dr. Robert Biswas-Diener is the senior editor of the Noba Project and author of more than 50 publications on happiness and other positive topics. His latest book is The Upside of Your Dark Side.