Facial Coverings and COVID-19: Reality Meets Theory and Then What?

Posted September 2, 2020

By Lynn White

The Task at Hand

The overwhelming consensus among scientists and medical professionals is that the spread of COVID-19 could be curtailed through the “simple” act of wearing a face covering. Yet, in the United States, we have seen a remarkable resistance to dawning a mask, suggesting this behavior is anything but simple. Understanding why poses a significant challenge and a necessary first step to effect change. A good place to start is the university classroom. Indeed, people in this demographic have come under recent criticism. Remember the distressing scenes of university students partying and “letting loose” on the sandy beaches of Florida during spring break of 2020? Many such instances followed. As a health psychologist and university professor, I wondered if I could use these events to: 1) effectively teach a health behavior theory through a guided activity; 2) use this health behavior theory to increase the students’ self-awareness of their own behaviors and contributory variables; and 3) help students to see how individuals contribute to public health and our shared responsibility for the wellbeing of the people around us.

The Health Belief Model

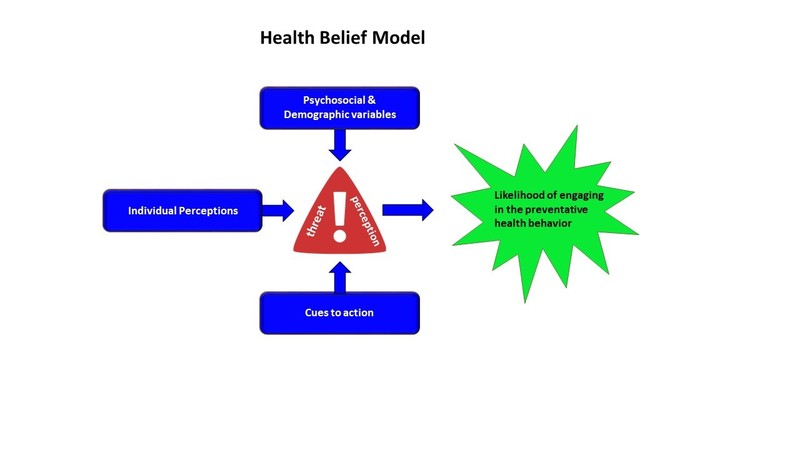

(HBM)in the 1950s and 60s. Working for the United States Public Health Service, they set out to explain why so many people in the United States refused to be vaccinated (at no cost) for tuberculosis. The HBM maintains that an individual’s perception of threat predicts whether they will or will not engage in a health behavior to mitigate that threat (see figure below). Several variables feed into the perception of threat and these are grouped into three categories: psychosocial and demographic variables, individual perceptions, and cues to action (Rosenstock,1966). Psychosocial variables include such things as personality, social norms, intelligence, self-efficacy, and past experiences. Demographic variables include age, sex, SES, and religious affiliation, among others. Individual perceptions center around susceptibility, severity, benefits of preventative action, and barriers of preventative action associated with the target behavior. Cues to action refer to internal and external stimuli that trigger or otherwise encourage the health behavior. Though certainly not perfect, research does support the utility of the HBM for predicting whether individuals will engage in preventative health behaviors (see Conner & Norman, 2015).

Teaching and Using the Health Belief Model Pre-COVID

I teach the HBM and many other similar theories in my health psychology classes. I am likely not the only one to have heard students claim that theories are only just that, and that they have little relevance to the “real” world. For years, I have been using a class activity to try and challenge this belief. I do not think I was very successful. To engage students, the activity was to use the HBM to elucidate the variables that predict the likelihood of participating (or not) in a specific health prevention behavior. I randomly placed students in groups of 4-5 and tasked them with taking one of two positions – either for or against enacting a positive health behavior. They would then use the HBM to support their assigned position. I asked the students to reflect on the three variable categories that feed into the perception of threat and write down specific attitudes, situations, and experiences that would increase threat (and make executing the health behavior more likely) or decrease threat (and make executing the health behavior less likely). Toward the end of the class period, each group shared their answers with the entire class. It was my hope that students would empathize with both positions, but ultimately see that the variables so many of us use to avoid positive health actions are typically excuses and not reasons. But there was a problem. The behaviors I assigned in the past included sunscreen use and wearing a seatbelt. Important health behaviors, right? Well, not so much in the eyes of twenty-something year-olds. Beyond trying to please the somewhat enthusiastic teacher at the front of the room (i.e., me), there was little motivation to dive deep and invest much energy into the activity. They simply did not seem to care. The activity came and went, soon forgotten.

Teaching and Using the Health Belief Model in the Midst of COVID

Whilst teaching health psychology in June 2020, I had an epiphany. Sunscreen and seatbelt use are not that relevant to people who refrain from spending time outdoors and to people who only use public transportation. COVID, on the other hand, is impacting virtually everyone globally. Not only is COVID and its transmission affecting our behavior, but the reverse is true. To the extent that people refuse to wear masks and/or socially distance, we are facilitating the spread of the virus. Recognizing this, I guessed that I finally had a shared experience and concern that everyone would agree is relevant. I saw an opportunity to use mask wearing to more fully engage students in the HBM activity and improve learning outcomes. I hoped that students would see how this theory could help explain their own and others’ mask-wearing behaviors. Finally, I hoped that this would increase favorable attitudes toward mask wearing and promote an attitude of shared responsibility for public health.

Modifications to Accommodate the Pandemic

Because of personal health concerns, I elected to teach my summer course online. Other than “zooming in” synchronously for 30 minutes twice weekly, students worked independently on the course. Given stress levels were uniformly high, I modified the HBM activity to not require group work. This necessitated other changes to the basic activity. Instead of working through the HBM from a singular position, either for or against mask wearing, each student had to assume both. I had each student create a worksheet (which they later shared with me) listing all their psychosocial and demographic variables, their individual perceptions, and cues to action that they believed would impact their decision to wear OR not wear a mask in public. They then had to assess the likelihood that they would routinely wear a facial covering.

The Results

If this was an experiment and the author submitted it for publication, I would reject it if only for the many uncontrolled confounds within. Nevertheless, I want to share what I found with you because this is the first time I have seen this activity: a) solicit answers which show deep thought and rigorous effort; b) motivate students to see an application beyond themselves; and c) show evidence of civic-mindedness. Aside from record-breaking completion rates for this activity, students’ answers were consistent with my belief that the activity “worked”. Some of their comments included:

I was reminded that I am part of a society that coexists and works together to overcome challenges. This activity convinced me to do my part in society and change my behavior in order to make this society a better place.

Nearly all of these variables make me want to enforce the behavior of wearing a mask in public… When I weigh the negative against the positive variables, I realize that wearing a mask in public is important for society’s health.

I discovered what my individual perceptions about the benefits of wearing a mask are. I realized that as I typed out some of the barriers why I wouldn't (or don't sometimes) wear a mask in public, most of them were excuses rather than valid reasons.

There probably needs to be better communication and more of a consensus between the government and health officials regarding wearing the mask. Policies should be mandated and enforced with repercussions for those who do not wear a mask in public.

This model is a great way to show how certain beliefs and factors can impact what people do. But also shows us what we can do to change those beliefs with cues that can make a difference in how we respond.

Overall, the attitudes of those college students who partied on the Florida beaches must be changed and their perception of their susceptibility, the severity and the threat of this virus must be increased exponentially.

Keep in mind that at no point did I instruct students explicitly or implicitly to reflect on societal implications or public health. The activity seemed to lend itself to these conclusions. Also, not everyone spoke in such civic-minded ways. Nevertheless, the fact that many did is encouraging.

Variations to the Activity

I chose the HBM for this activity, but I suspect that other health models would work well. In the past, I have used the Theory of Planned Behavior and found that the variables students identify are typically the same, regardless of which model they use. When face-to-face classes once again become safe, I plan to repeat the HBM activity but return to the group approach. I suspect that hearing what others think and believe might promote even more civic-minded thinking. Then again, students might feel inhibited to speak freely on such a controversial topic as mask wearing. Of course, other health prevention behaviors with a global impact could be used. For example, students might be asked to reflect on social distancing or vaccinations.

Key Takeaways

As educators, whenever possible we need to think beyond what the students will learn and apply only to themselves. We can combine the objectives of helping students learn through application and increasing civic-mindedness. Not all activities lend themselves to this. Finding timely events which impact all students may be an important consideration.

References

Conner, M., & Norman, P. (2015). Health belief model. In Predicting and changing health behaviour: Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models (3rd ed., pp. 30–69). Open University Press.

Rosenstock, I. M. (1966). Why people use health services. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 44, 94–127.

Bio

Lynn H. White is a Professor of Psychology at Southern Utah University. She received her Bachelor’s degree from Bishops University in Lennoxville, Quebec, Canada, and her Master’s and Ph.D. in Physiological and Comparative Psychology from McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. She is a health psychologist whose teaching interests include health psychology, stress and pain, brain and behavior, and statistics. Dr. White is a strong advocate of experiential learning. She has established both department and university-specific undergraduate research programs. Dr. White is the recipient of teaching and mentoring awards at the university and regional levels.