Using survey software to engage students: Ethical dilemma decision tree

Posted December 12, 2018

By Jennifer Gibbs with Louisa Nkrumah

I’ve been teaching criminal justice courses both in residence and online for six years. With so many stories about police events in the news, my students and I have plenty of real-world examples to discuss. Unfortunately, from time to time, these conversations can seem superficial.

This is especially the case when we cover the ethical dilemma involving police accepting gratuities – such as free meals or a free cup of coffee. Some students agree that police should be able to accept gratuities because the public is showing appreciation for their service and it would be impolite to decline such a generous offer. Other students argue that police should not accept gratuities because these gifts can be a slippery slope to corruption.

To deepen the discussion, we must move beyond these cursory arguments. For example, how might other officers react when one turns down a free coffee that all other officers have accepted? Might that lead other officers to distrust the refuser? Might that have implications in other areas of the workplace? Maybe so, maybe not; but, this is a conversation worth having. And too often in my class we don’t have it.

I turned to my instructional designer, Louisa, for advice. We discussed ways to increase student engagement. Ultimately, we thought a decision tree activity might lead to deeper conversations on this topic.

Display Logic: Useful Feature of Survey Software

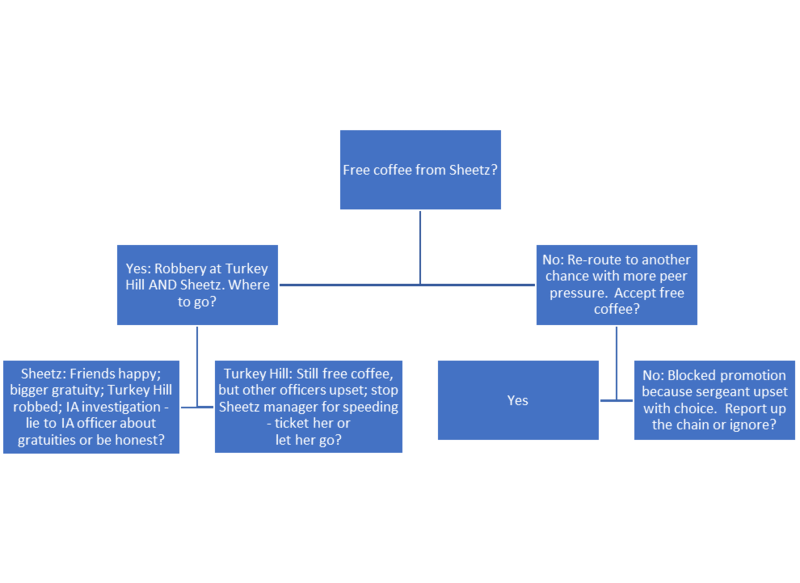

I had several conversations with students in my office about what might happen if a police officer accepted a free cup of coffee. Across many such discussions, I developed a decision tree with various paths based on the decisions made. I mapped it out in Word; in retrospect, Excel might have been an easier tool. Excel has the ability to hide long text in one small cell while also displaying it in full in the formula box above when clicking on the individual cell.

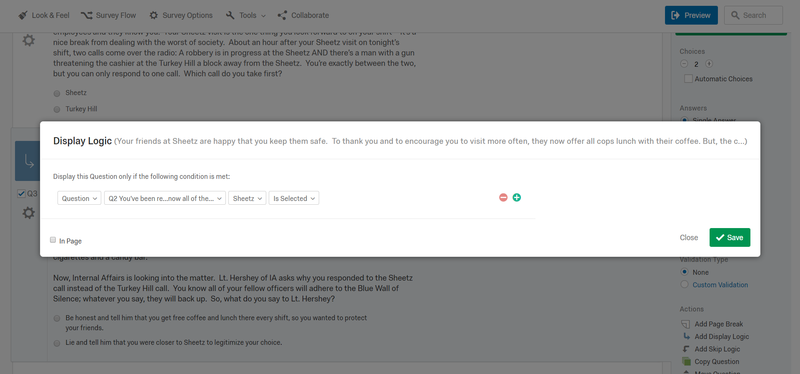

Penn State, where I teach, offers employees licenses to use Qualtrics. Other survey software has similar attributes. However, having used Qualtrics on past research, I was familiar with some of its features. One, in particular, is “display logic" (see Figure 1). Display logic only shows an item on some condition set by the programmer.

This feature is especially useful for developing decision trees, where we want the student to go to a scenario based on a previous response. For example, the opening scenario asks whether the student, as a rookie officer, would accept a free cup of coffee when offered:

You are a rookie officer on the afternoon shift. You stop for coffee at the Sheetz on your beat, where you meet up with Joe, another officer who’s been on the job for about 12 years. You and Joe walk up to the register to pay for your coffee and the cashier refuses to accept your money: “Your money is no good here! We appreciate your service. Coffee’s on us”. Joe thanks the cashier and tells you, “It’s nice to be appreciated once in a while. That’s why all the guys stop here for coffee”. What do you do?

If a student does not accept a free cup of coffee, s/he is redirected to a similar scenario with more peer pressure to accept; if s/he continues to decline the free cup of coffee, other officers progressively withdraw trust, leading to dangerous situations.

If a student accepts the free cup of coffee, the next scenario that will display asks how s/he would respond to two incidents:

You’ve been regularly going to Sheetz for the free coffee for some time now. You know all of the Sheetz employees and they know you. Your Sheetz visit is the one thing you look forward to on your shift – it’s a nice break from dealing with the worst of society. About an hour after your Sheetz visit on tonight’s shift, two calls come over the radio: A robbery is in progress at the Sheetz AND there’s a man with a gun threatening the cashier at the Turkey Hill a block away from the Sheetz. You’re exactly between the two, but you can only respond to one call. Which call do you take first?

If the student responds to Sheetz, the next scenario increases the gratuities officers are offered to both lunch and coffee. However, the Turkey Hill was robbed and the cashier was injured, prompting an Internal Affairs investigation because of the slow response time. If the student responds to Turkey Hill, the Sheetz employees rescind the free coffee offer for all officers and now other officers are upset with the student rookie.

Below is a sample of the first few decisions. To test this out for yourself, go to bit.ly/decisiontree-lilly2018.

Once the decision tree was entered into Qualtrics, I asked police officer friends to review the scenarios for a reality check. While some scenarios are a bit over the top with the intention to drive the point home to students, they agreed the scenarios are possible.

As one can see, the progressive nature of the decision trees leads students to deeper understanding of the ethical decision-making process. The tool accomplishes many objectives: it allows students to consider angles they might naturally overlook, it emphasizes ethical decision making as a process rather than as blindly following rules, and it provides insight into real world policing issues.

Deeper Discussions

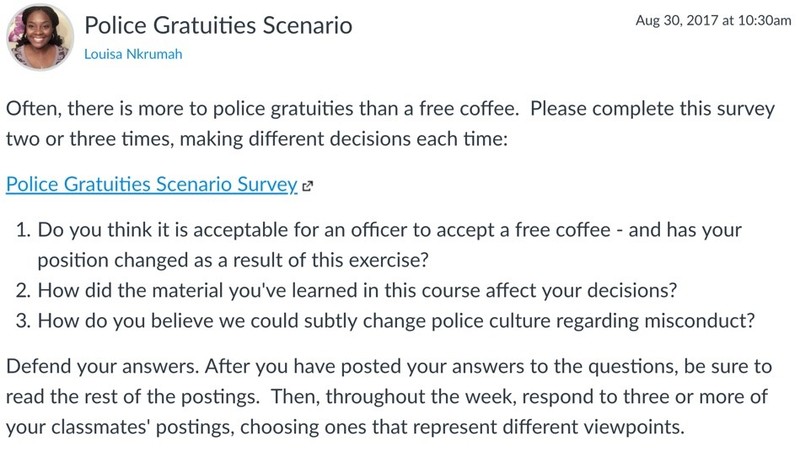

For class participation, students are asked to complete the decision tree multiple times, making different decisions each time. Then, students post their responses to a prompt on the online discussion board. (For the classes held in-residence, students are required to post to weekly discussion prompts online.)

Overall, this was a welcome addition to the class discussions and a fruitful way to use survey software.

Bios:

Dr. Jennifer Gibbs is an Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice in the School of Public Affairs at Penn State Harrisburg, where she studies policing topics, including public attitudes toward police, violence against police and police recruitment and hiring. Her work on social distance and attitudes toward police, co-authored with Dr. Jonathan Lee, was recognized in the 2016 Emerald Literati Network Awards for Excellence.

Louisa Nkrumah is a Learning Experience Designer at the University of Maryland, College Park in their Teaching and Learning Transformation Center (TLTC). In her role, she provides instructional consulting, support, and training, learning technologies support and implementation, and instructional design support. Prior to joining the TLTC in June 2018, Louisa was an instructional designer at Penn State Harrisburg, where she collaborated with faculty to design, develop, and revise courses for the online Criminal Justice and Homeland Security programs via Penn State World Campus. Louisa holds a B.S. in Applied Behavioral Sciences and an M.Ed. in Training and Development, both from Penn State Harrisburg.