Mild or Spicy? How students prefer their instruction

Posted January 3, 2019

By Kentina Smith

“Be the guide on the side, not the sage on the stage. I am the guide who creates the learning experience and then steps back to let learners take over”. – Sharon Bowman

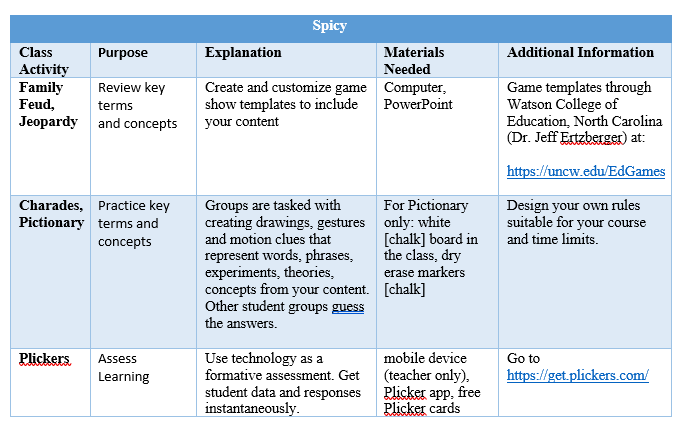

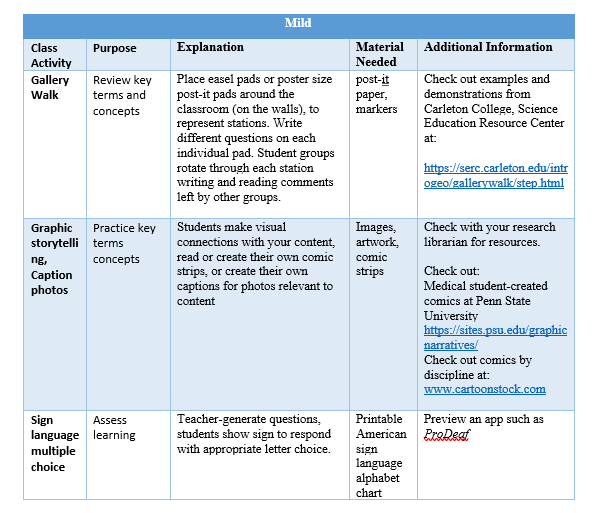

Do your students ever nod off, watch the clock, or retreat to their phones during lecture? In this fast-paced digital age it can be challenging to keep student attention. Harder still is engaging interest and helping students make their thinking visible. A little innovation can go a long way toward increasing student engagement in three areas: doing (behavioral), thinking (cognitive), and feeling (emotional, interest). If you are ready to plunge in and try active engagement in your lessons, check out the spicy strategies. If these strategies are a bit too much for your instructional palette, check out the milder alternatives.

Dealing with Student and Faculty Resistance to Active Learning

Students and instructors alike sometimes turn up their noses at these types of learning activities. Admittedly, they are artificial and so can sometimes seem “hokey” or even frivolous. In her book called Learner-Centered Teaching, Maryellen Weimer details dealing with the “nuts and bolts” of implementation and addresses both faculty and student resistance. Weimer recognizes that these types of activities involve additional planning and ask more of instructors than do traditional lectures.

Her advice, when students scoff at active approaches, is “don’t take it personally.” My approach is to be upfront with students at the start of the semester. During the first day of class, I inform students, model, and demonstrate my teaching philosophy which includes active learning and an inclusive environment. Be open with students about the purpose of active strategies and tell students ahead of time when and how they will be implemented.

By contrast, Weimer’s advice for dealing with faculty resistance is “do not seek to convert the masses.” Your colleagues exist in their own, unique web of tenure, research, personal style, and so forth. These activities are not for every teaching style and so it is best that you limit your discussion of them to like-minded colleagues. Perhaps most importantly, Weimer emphasizes the importance of documenting the impact of your approaches.

So what will it be, spicy or mild?

Bio

My area of scholarship is educational psychology. I have been in the field of education for more than 20 years and hold an advanced professional certification in teaching. My experience has involved working with toddlers, managing literacy programming, inclusion classroom co-teaching, mentoring teachers, working with adolescents’ social and emotional skills and teaching in middle schools and college.

References

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., Lovett, M. C., DiPietro, M., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How Learning Works. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bowman, S. (2014). Presenting with Pizzazz. Glenbrook: Bowperson Publishing.

Marin, A. (n.d.). Game ideas for the psychology classroom. Retrieved from https://www.pearsoned.com/wp-content/uploads/Marin...

Weimer, M. (2002). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five keys changes to practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass .

Wilbert J. McKeachie, M. S. (2006). McKeachie's teaching tips: strategies, research, and theory for college and university teachers. Belmont: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.