Oral Exams in Large Online Classes

Posted March 10, 2021

By Brianne R. Coulombe

Last year, I began entertaining the idea of swapping out traditional multiple-choice final exams for oral exams. You read that correctly: I began considering having my undergraduate students do the type of oral exams most commonly associated with dissertation defenses. I know what you’re thinking: “I work at a big university and even my smallest classes have 150 students in them. There is no way that I can make an oral exam work for a class that large.” I thought the same thing when I came across this article (https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1218283.pdf), in which instructors in an anthropology department used an oral exam in a class of ~250 students. Inspired by this team of academics, I piloted a similar exam in an upper-division developmental psychology course of 150 students at a large research institution, and it actually saved time. Here’s how I did it.

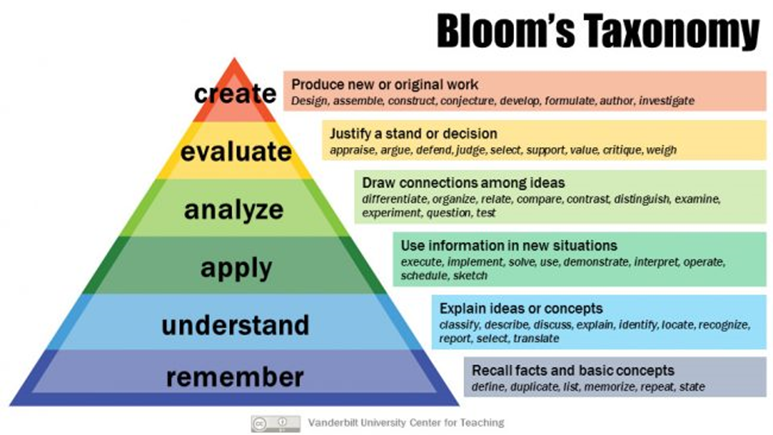

First, I want to talk a little bit about the goal of assessment. If you’ve written a multiple-choice exam, you’ve probably caught yourself trying to make sure that the questions aren’t too easy or too tricky. At the end of the day, it’s downright difficult to write a good multiple-choice question that assesses students’ full engagement with the material. It’s much easier to write more surface-level questions that ask students to show what they know. On Bloom’s taxonomy of learning, multiple-choice questions—especially of the “factual” and “conceptual” variety—primarily address the lowest two rungs: remember and understand. What we want, instead, is for students to leave our classes at the top of the taxonomy, with the skills to create, evaluate, and analyze ideas that they learned in our class and take that full knowledge forth into future classes.

This goal can be accomplished through the use of essay questions, which ask students to draw connections between class concepts or to defend a thesis using evidence learned in class. However, grading essay questions can be both time-consuming and difficult to calibrate fairly. Oral exams mitigate both of these challenges. First, because grading happens during the administration of the exam itself, professors and teaching assistants don’t have to spend hours proctoring and then more hours grading. Second, this method can level the playing field where communication skills are concerned because you can ask students to clarify their meaning on the spot.

Here’s how my oral exam process worked. Students were asked to answer one of five randomly-chosen questions that were all provided in the syllabus on the very first day of class. Each question asked them to take a position on a controversy in developmental psychology and support their position with relevant empirical examples from the course. Rubrics were also provided on the first day, so students understood exactly what we were looking for in a strong response. Students were understandably anxious about this foreign testing format, but my teaching assistants and I worked together to scaffold their learning in several ways.

First, at least once every class, I connected a concept directly to one of the exam questions to show students how they might incorporate class examples into their arguments. This served the dual benefit of illustrating what was expected on the final exam and reminding students that studying for this exam cannot be left to the last minute.

Second, for their midterm exam, students were asked to write a response (~500 words) to one final exam question of their choosing. Whichever question they chose would not be asked of them on their final exam. That meant that if there was a question that students found particularly daunting, they could write it up for their midterm to ensure it would not be asked on their final exam. Teaching assistants provided detailed feedback on these responses to show students where they could have improved their answers.

Finally, the last day of class was spent in small groups (or breakout rooms via Zoom) with students working together to quiz each other and strengthen their answers with the help of a teaching assistant.

On the day of the final exam, students signed up for a 3-minute time slot with me or one of my teaching assistants, wherein they answered one of five questions which was randomly chosen for them on the day of the exam. Students were allowed to bring any notes they wished, including full write-ups of each question. Most questions could be fully answered in about 90-180 seconds, so we had a little bit of time afterward to ask clarifying questions or to prompt students to provide additional examples which bolstered grades. Grading was weighted with 80% for content and 20% for comfort and ease of delivery of their material. The entire exam including proctoring and grading took only 8 hours of instructional time. I split the testing load with my three teaching assistants, so with only 2 hours of work each, we proctored and graded a high-level final exam in an upper-division course of 150 students.

This exam format is easily adjusted for in-person and online course offerings. Due to COVID-19, we proctored all exams using Zoom, but this would have worked just as well in an office or classroom. Even in a class of 150, we had only 1 student whose technology failed her during the exam, and we were able to reschedule her later in the day. In the future, I would provide students with a google voice number to conduct the exam by phone and build in a 5-10 minute pocket of time in each hour to make up for lateness and technical difficulties. Overall, grades were higher in this format than in previous years when I used traditional multiple-choice/short-answer formats by about 5%, and students reported feeling confident that they’d retain the material for a long time to come.

After using this exam format once, I can definitively say that I’m hooked! Overall, this was less work for me as an instructor and it required more thorough engagement from my students. Moreover, this exam format helped students to develop skills that translate into other classes and fields of study. This assessment pushed students to form an idea and defend it using scientific evidence, and to communicate their thoughts clearly and concisely. For me, helping students hone that skill while also deeply learning about a new topic (i.e., developmental psychology) is exactly what higher education is about.

Bio

Brianne Coulombe is a 5th year PhD student in the Developmental Psychology program at the University of California, Riverside. Her research interests include the development of prosocial behavior (i.e., behavior intended to benefit others), children’s social interactions in school settings, and risk and resilience. When she isn’t working on her research or devising creative activities and assignments for her classroom, you can find her browsing food blogs to find new recipes to try in the kitchen or, when the pandemic is over, practicing acroyoga outside with her friends.