Human Sexual Anatomy and Physiology

By Don Lucas and Jennifer FoxNorthwest Vista College

It’s natural to be curious about anatomy and physiology. Being knowledgeable about anatomy and physiology increases our potential for pleasure, physical and psychological health, and life satisfaction. Beyond personal curiosity, thoughtful discussions about anatomy and physiology with sexual partners reduces the potential for miscommunication, unintended pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections, and sexual dysfunctions. Lastly, and most importantly, an appreciation of both the biological and psychological motivating forces behind sexual curiosity, desire, and the capacities of our brains can enhance the health of relationships.

Learning Objectives

- Explain why people are curious about their own sexual anatomies and physiologies.

- List the sexual organs of the female and male.

- Describe the sexual response cycle.

- Distinguish between pleasure and reproduction as motives behind sexuality.

- Compare the central nervous system motivating sexual behaviors to the autonomic nervous system motivating sexual behaviors.

- Discuss the relationship between pregnancy and birth control.

- Analyze how sexually transmitted infections are associated with sexual behaviors.

- Understand the effects of sexual dysfunctions and their treatments on sexual behaviors.

Introduction

Most people are curious about sex. Google processes over 3.5 billion search queries per day (Google Search Statistics)—tens of millions of which, performed under the cloak of anonymity, are about sex. What are the most frequently asked questions concerning sex on Google? Are they about extramarital affairs? Kinky fantasies? Sexual positions? Surprisingly, no. Usually they are practical and straightforward, and tend to be about sexual anatomy (Stephens-Davidowitz, 2015)—for example, “How big should my penis be?” and, “Is it healthy for my vagina to smell like vinegar?” Further, Google reveals that people are much more concerned about their own sexual anatomies than the anatomies of others; for instance, men are 170 times more likely than women to pose questions about penises (Stephens-Davidowitz, 2015). The second most frequently asked questions about sex on Google are about sexual physiology—for example, “How can I make my boyfriend climax more quickly?” “Why is sex painful?” and, “What exactly is an orgasm?” These searches are clear indicators that people have a tremendous interest in very basic questions about sexual anatomy and physiology.

However, the accuracy of answers we get from friends, family, and even internet “authorities” to questions about sex is often unreliable (Fuxman et al., 2015; Simon & Daneback, 2013). For example, when Buhi and colleagues (2010) examined the content of 177 sexual-health websites, they found that nearly half contained inaccurate information. How about we—the authors of this module—make you a promise? If you learn this material, then we promise you won’t need nearly as many clandestine Google excursions, because this module contains unbiased and scientifically-based answers to many of the questions you likely have about sexual anatomy and physiology.

Are you ready for a new twist on “sexually-explicit language”? Even though this module is about a fascinating topic—sex—it contains vocabulary that may be new or confusing to you. Learning this vocabulary may require extra effort, but if you understand these terms, you will understand sex and yourself better.

Masters and Johnson

Although people have always had sex, the scientific study of it has remained taboo until relatively recently. In fact, the study of sexual anatomy, physiology, and behavior wasn’t formally undertaken until the late 19th century, and only began to be taken seriously as recently as the 1950’s. Notably, William Masters (1915-2001) and Virginia Johnson (1925-2013) formed a research team in 1957 that expanded studies of sexuality from merely asking people about their sex lives to measuring people’s anatomy and physiology while they were actually having sex. Masters was a former Navy lieutenant, married father of two, and trained gynecologist with an interest in studying sex wor. Johnson was a former country music singer, single mother of two, three-time divorcee, and two-time college dropout with an interest in studying sociology. And yes, if it piques your curiosity, Masters and Johnson were lovers (when Masters was still married); they eventually married each other, but later divorced. Despite their colorful private lives they were dedicated researchers with an interest in understanding sex from a scientific perspective.

Masters and Johnson used primarily plethysmography (the measuring of changes in blood- or airflow to organs) to determine sexual responses in a wide range of body parts—breasts, skin, various muscle structures, bladder, rectum, external sex organs, and lungs—as well as measurements of people’s pulse and blood pressure. They measured more than 10,000 orgasms in 700 individuals (18 to 89 years of age), during sex with partners or alone. Masters and Johnson’s findings were initially published in two best-selling books: Human Sexual Response, 1966, and Human Sexual Inadequacy, 1970. Their initial experimental techniques and data form the bases of our contemporary understanding of sexual anatomy and physiology.

The Anatomy of Pleasure and Reproduction

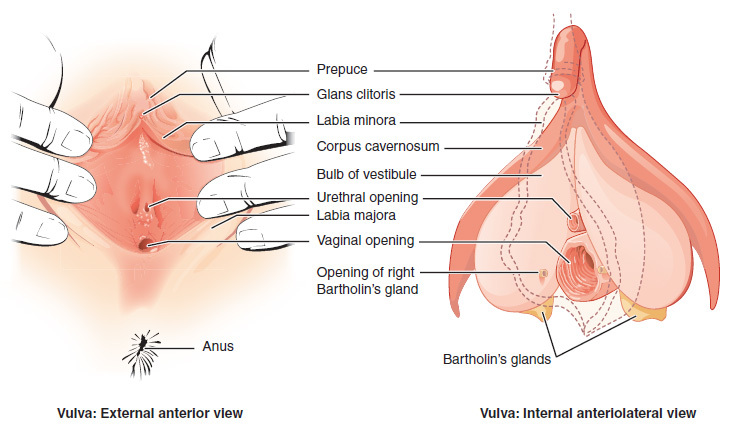

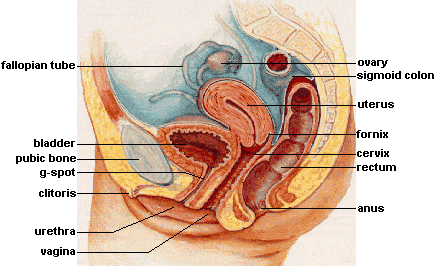

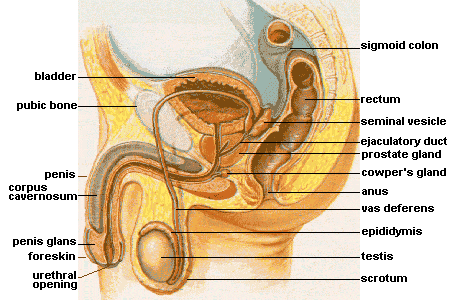

Sexual anatomy is typically discussed only in terms of reproduction (see e.g., King, 2015). However, reproduction is only a (small) part of what drives us sexually (Lucas & Fox, 2018). Full discussions of sexual anatomy also include the concept of pleasure. Thus, we will explore the sexual anatomies of females (see Figures 1a and 1b) and males (see Figure 2) in terms of their capabilities for both reproduction and pleasure.

Female Anatomy

Many people find female sexual anatomy curious, confusing, and mysterious. This may be because so much of it is internal (inside the body), or because—historically—women have been expected to be modest and secretive regarding their bodies.

Perhaps the most visible structure of female sexual anatomy is the vulva. The primary functions of the vulva are pleasure and protection. The vulva is composed of the female’s external sex organs (see Figure 1a). It includes many parts:

(a) the labia majora—the “large lips” enclosing and protecting the female’s internal sex organs;

(b) the labia minora—the“small lips” surrounding and defining the openings of the vagina and urethra;

(c) the minor and major vestibular glands (VGs).

The minor VGs—also called Skene's glands (not pictured), are on the wall of the vagina and are associated with female ejaculation, and mythologically associated with the G-Spot (Kilchevsky et al., 2012; Wickman, 2017). The major VGs—also called Bartholin's glands—are located just to the left and right of the vagina and produce lubrication to aid in sexual intercourse. Most females—especially postmenopausal females—at some time in their lives report inadequate lubrication, which, in turn, leads to discomfort or pain during sexual intercourse (Nappi & Lachowsky, 2009). Extending foreplay and using commercial water-, silicone-, or oil-based personal lubricants are simple solutions to this common problem.

The clitoris and vagina are considered parts of the vulva as well as internal sex organs (see Figure 1b). They are the most talked about organs in relation to their capacities for female pleasure (e.g., Jannini et al., 2012). Most of the clitoris, which is composed of 18 parts with an average overall excited length of about four inches, cannot be seen (Ginger & Yang, 2011; O'Connell et al., 2005). The visible parts—the glans and prepuce—are located above the urethra and join the labia minora at its pinnacle. The clitoris is highly sensitive, composed of more than 8,000 sensory-nerve endings, and is associated with initiating orgasms; 90% of females can orgasm by clitoral stimulation alone (O'Connell et al., 2005; Thompson, 2016).

The vagina, also called the “birth canal,” is a muscular canal that spans from the cervix to the introitus. It has an average overall excited length of about four and a half inches (Masters & Johnson, 1966) and has two parts: First, there is the inner two-thirds (posterior wall)—formed during the first trimester of pregnancy. Second, there is the outer one-third of the vagina (anterior wall). It is formed during the second trimester of pregnancy and is generally more sensitive than the inner portion, but dramatically less sensitive than the clitoris (Hines, 2001). Only between 10% and 30% of females achieve orgasms by vaginal stimulation alone (Thompson, 2016). At each end of the vagina are the cervix (the lower portion of the uterus) and the introitus (the vaginal opening to the outside of the body). The vagina acts as a transport mechanism for sperm cells coming in, and menstrual fluid and babies going out. A healthy vagina has a pH level of about four, which is acidic. When the pH level changes, often due to normal circumstances (e.g., menstruation, using tampons, sexual intercourse), it facilitates the reproduction of microorganisms that often cause vaginal odor and pain (Anderson, Klink & Cohrssen, 2004). This potential problem can be solved with over-the-counter vaginal gels or oral probiotics to maintain normal vaginal pH levels (Tachedjiana et al., in press).

The primary functions of the internal sex organs of the female are to store, transport, and keep ovum cells (eggs) healthy; and produce hormones (see Figure 1b). These organs include:

(a) the uterus (or womb)—where human development occurs until birth;

(b) the ovaries—the glands that house the ova (eggs; about two million; Faddy et al., 1992) and produce progesterone, estrogen, and small amounts of testosterone;

(c) the fallopian tubes—where fertilization is most likely to occur. These tubes allow for ovulation (about every 28 days), which is when ova travel from the ovaries to the uterus. If fertilization does not occur, menstruation begins. Menstruation, also known as a “period,” is the discharge of ova along with the lining of the uterus through the vagina, usually taking several days to complete.

Male Anatomy

The most prominent external sex organ for the male is the penis. The penis’s main functions are initiating orgasm, and transporting semen and urine from the body. On average, a flaccid penis is about three and a half inches in length, whereas an erect penis is about five inches (Veale et al., 2015; Wessells, Lue & McAninch, 1996). If you want to know the length of a particular male’s erect penis, you’ll have to actually see it—because there are no reliable correlations between the length of an erect penis and (a) the length of a flaccid penis, (b) the lengths of other body parts—including feet, hands, forearms, and overall height—or (c) race and ethnicity (Shah & Christopher, 2002; Siminoski & Bain, 1993; Veale et al., 2015; Wessells, Lue & McAninch, 1996). The penis has three parts: the root, shaft, and glans. Foreskin covers the glans, or head of the penis, except in circumcised males. The glans penis is highly sensitive, composed of more than 4,000 sensory-nerve endings, and associated with initiating orgasms (Halata, 1997). Lastly, it has the urethral opening that allows semen and urine to exit the body.

In addition to the penis, there are other male external sex organs that have two primary functions: producing hormones and sperm cells. The scrotum is the sac of skin behind and below the penis containing the testicles. The testicles (or testes) are the glands that produce testosterone, progesterone, small amounts of estrogen, and sperm cells.

Many people are surprised to learn that males also have internal sex organs. The primary functions of male internal sex organs are transporting sperm cells, keeping sperm cells healthy, and producing semen—the fluid in which sperm cells are transported. The male’s internal sex organs include:

(a) the epididymis, which is a twisted duct that matures, stores, and transports sperm cells into the vas deferens;

(b) the vas deferens—a muscular tube that transports mature sperm to the urethra, except in males who have had a vasectomy;

(c) the seminal vesicles—glands that provide energy for sperm cells to move. This energy is in the form of sugar (fructose) and it composes about 75% of the semen. Sperm cells only compose about 1% of the semen (Owen & Katz, 2005);

(d) the prostate gland, which provides additional fluid to the semen that nourishes the sperm cells; and the Cowper's glands, which produce a fluid that lubricates the urethra and neutralizes any acidity due to urine;

(e) the urethra—the tube that carries urine and semen outside of the body.

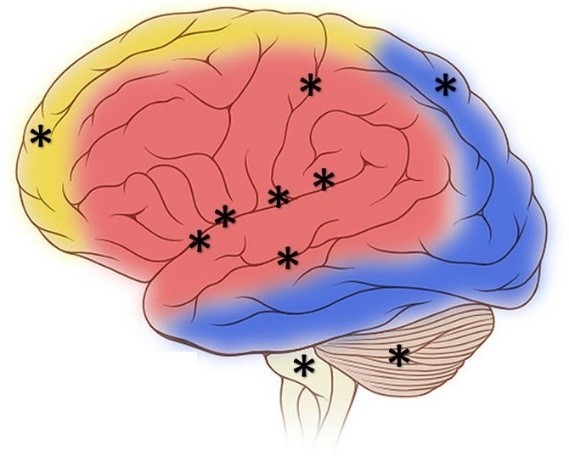

Sex on the Brain

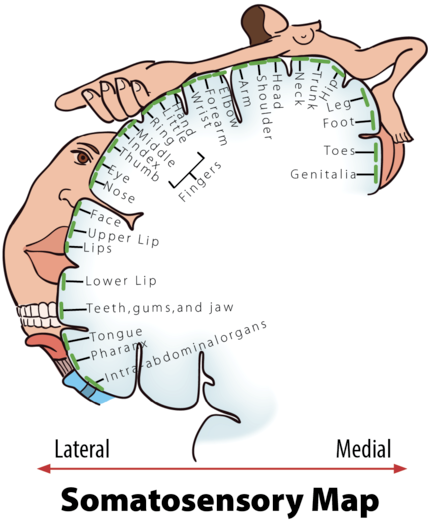

At first glance—or touch for that matter—the clitoris and penis are the parts of our anatomies that seem to bring the most pleasure. However, these two organs pale in comparison to our central nervous system’s capacity for pleasure. Extensive regions of the brain and brainstem are activated when a person experiences pleasure, including: the insula, temporal cortex, limbic system, nucleus accumbens, basal ganglia, superior parietal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and cerebellum (see Figure 3, Ortigue et al., 2007). Neuroimaging techniques show that these regions of the brain are active when patients have spontaneous orgasms involving no direct stimulation of the skin (e.g., Fadul et al., 2005) and when experimental participants self-stimulate erogenous zones (e.g., Komisaruk et al., 2011). Erogenous zones are sensitive areas of skin that are connected, via the nervous system, to the somatosensory cortex in the brain.

The somatosensory cortex (SC) is the part of the brain primarily responsible for processing sensory information from the skin. The more sensitive an area of your skin is (e.g., your lips), the larger the corresponding area of the SC will be; the less sensitive an area of your skin is (e.g., your trunk), the smaller the corresponding area of the SC will be (see Figure 4, Penfield & Boldrey, 1937). When a sensitive area of a person’s body is touched, it is typically interpreted by the brain in one of three ways: “That tickles!” “That hurts!” or, “That…you need to do again!” Thus, the more sensitive areas of our bodies have greater potential to evoke pleasure. A study by Nummenmaa and his colleagues (2016) used a unique method to test this hypothesis. The Nummenmaa research team showed experimental participants images of same- and opposite-sex bodies. They then asked the participants to color the regions of the body that, when touched, they or members of the opposite sex would experience as sexually arousing while masturbating or having sex with a partner. Nummenmaa found the expected “hotspot” erogenous zones around the external sex organs, breasts, and anus, but also reported areas of the skin beyond these hotspots: “[T]actile stimulation of practically all bodily regions trigger sexual arousal….” Moreover, he concluded, “[H]aving sex with a partner…”—beyond the hotspots—“…reflects the role of touching in the maintenance of…pair bonds.”

Physiology and the Sexual Response Cycle

The brain and other sex organs respond to sexual stimuli in a universal fashion known as the sexual response cycle (SRC; Masters & Johnson, 1966). The SRC is composed of four phases:

- Excitement: Activation of the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system defines the excitement phase; heart rate and breathing accelerates, along with increased blood flow to the penis, vaginal walls, clitoris, and nipples. Involuntary muscular movements (myotonia), such as facial grimaces, also occur during this phase.

- Plateau: Blood flow, heart rate, and breathing intensify during the plateau phase. During this phase, often referred to as “foreplay,” females experience an orgasmic platform—the outer third of the vaginal walls tightening—and males experience a release of pre-seminal fluid containing healthy sperm cells (Killick et al., 2011). This early release of fluid makes penile withdrawal a relatively ineffective form of birth control (Aisch & Marsh, 2014). (Question: What do you call a couple who use the withdrawal method of birth control? Answer: Parents.)

- Orgasm: The shortest but most pleasurable phase is the orgasm phase. After reaching its climax, neuromuscular tension is released and the hormone oxytocin floods the bloodstream—facilitating emotional bonding. Although the rhythmic muscular contractions of an orgasm are temporally associated with ejaculation, this association is not necessary because orgasm and ejaculation are two separate physiological processes.

- Resolution: The body returns to a pre-aroused state in the resolution phase. Males enter a refractory period of being unresponsive to sexual stimuli. The length of this period depends on age, frequency of recent sexual relations, level of intimacy with a partner, and novelty. Because females do not have a refractory period, they have a greater potential—physiologically—of having multiple orgasms. Ironically, females are also more likely to “fake” having orgasms (Opperman et al., 2014).

Of interest to note, the SRC occurs regardless of the type of sexual behavior—whether the behavior is masturbation; romantic kissing; or oral, vaginal, or anal sex (Masters & Johnson, 1966). Further, a partner or environmental object is sufficient, but not necessary, for the SRC to occur.

Pregnancy

One of the potential outcomes of the SRC is pregnancy—the time a female carries a developing human within her uterus. How does this happen?

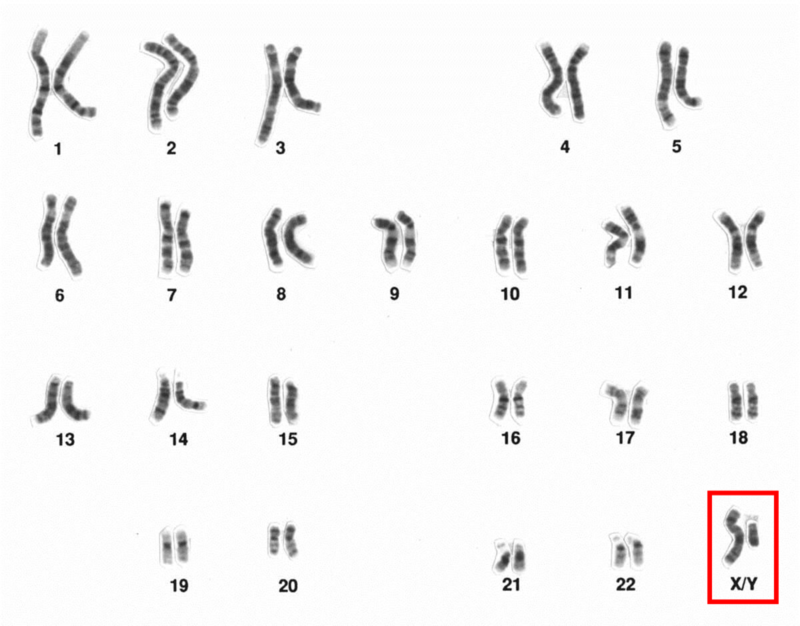

The process begins during vaginal intercourse when the male ejaculates, or releases semen. Each ejaculate contains about 300 million sperm cells. These sperm compete to make their way through the cervix and into the uterus. Conception typically occurs within a fallopian tube when a single sperm cell comes into contact with an ovum (egg). The sperm carries either an X- or Y-chromosome to fertilize the ovum—which, itself, usually carries an X-chromosome. These chromosomes, in combination with one another, are what determine a person’s sex. The combination of two X chromosomes produces a female zygote (fertilized ovum). The combination of an X and Y chromosome produces a male zygote. XX- or XY-chromosomes form your 23rd set of chromosomes (most humans have a total of 46 chromosomes) commonly referred to as your chromosomal sex or genetic sex.

Interestingly, at least 1 in every 1,000 conceptions results in a variation of chromosomal sex beyond the typical XX or XY sets. Some of these variations include, XXX, XXY, XYY, or even a single X (Dreger, 1998). In some cases, people may have unusual physical characteristics, such as being taller than average, having a thick neck, or being sterile (unable to reproduce); but in many cases, these individuals have no cognitive, physical, or sexual issues (Wisniewski et al., 2000). Almost 15 out of every 1,000 births are multiple births (twins, triplets, quadruplets, etc.). These can occur in a couple of ways. Dizygotic (fraternal) births are the result of a female releasing multiple ova of which more than one is fertilized by sperm. Because sperm carry either X or Y chromosomes, fraternal births can be any combination of sexes (e.g., two girls or a boy and a girl). They develop together in the uterus and are usually born within minutes of one another. Monozygotic (identical) births result from a special circumstance in which a fertilized ovum splits into multiple identical embryos and they develop simultaneously. Identical twins are, therefore, the same sex.

Hours after conception, the zygote begins dividing into additional cells. It then starts traveling down the fallopian tube until it enters the uterus as a blastocyst. The blastocyst implants itself within the wall of the uterus to become an embryo (Moore, Persaud & Torchia, 2016). However, the percentage of successful implantations remains a mystery. Researchers believe the failure rate to be as high as 60% (Diedrich et al., 2007). Failed blastocysts are eliminated during menstruation, often without the female ever knowing conception occurred.

Mothers are pregnant for three trimesters, a term that begins with their last menstrual period and ends about 40 weeks later; each trimester is 13 weeks. During the first trimester, most of the body parts of the embryo are formed, although at this stage they are not in the same proportions as they will be at birth. The brain and head, for example, account for about half of the body at this point. During the fifth and sixth weeks of gestation, the primitive gonads are formed. They eventually develop into ovaries or testes. Until the seventh week, the developing embryo has the potential of having either male (Wolffian ducts) or female (Mullerian ducts) internal sex organs, regardless of chromosomal sex. In fact, there is an innate tendency for all embryos to have female internal sex organs, unless there is the presence of the SRY gene, located on the Y-chromosome (Grumbach & Conte, 1998; Wizemann & Pardue, 2001). The SRY gene causes XY-embryos to develop testes (dividing cells from the medulla). The testes emit testosterone which stimulates the development of male internal sex organs—the Wolffian ducts transforming into the epididymis, seminal vesicles, and vas deferens. The testes also emit a Mullerian inhibiting substance, a hormone that causes the Mullerian ducts to atrophy. If the SRY gene is not present or active—typical for chromosomal females (XX)—then XX-embryos develop ovaries (dividing cells from the cortex) and the Mullerian ducts transform into female internal sex organs, including the fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix, and inner two-thirds of the vagina (Carlson, 1986). Without a burst of testosterone from the testes, the Wolffian ducts naturally deteriorate (Grumbach & Conte, 1998; Wizemann & Pardue, 2001).

During the second trimester, expectant mothers can feel movement in their wombs. This is known as quickening. Inside the uterus, the embryo develops fine hair all over its body (called lanugo) as well as eyelashes and eyebrows. Major organs, such as the pancreas and liver, begin fully functioning. By the 20th week of gestation, the external sex organs are fully formed, which is why “sex determination” using ultrasound during this time is more accurate than in the first trimester (Igbinedion & Akhigbe, 2012; Odeh, Ophir & Bornstein, 2008). Formation of male external sex organs (e.g., the penis and scrotum) is dependent upon high levels of testosterone, whereas female external sex organs (e.g., the outer third of the vagina and the clitoris) form without hormonal influences (Carlson, 1986). Levels of sex hormones, such as estrogen, testosterone, and progesterone, begin affecting the brain during this trimester, impacting future emotions, behaviors, and thoughts related to gender identity and sexual orientation (Swaab, 2004). It’s important to understand that the interactions of chromosomal sex, gonadal sex, sex hormones, internal sex organs, external sex organs, and brain differentiations during this developmental stage are too complex to readily conform to the familiar categories of sex, gender, and sexual orientation historically used to describe people (Herdt, 1996). Toward the end of the second trimester—at about the 26th week—is the age of viability, when survival outside of the uterus has a probability of more than 90% (Rysavy et al., 2015). Interestingly, technological advances and changes in hospital care have affected the age of viability such that viability is possible earlier in pregnancy (Rysavy et al., 2015).

During the third trimester, there is rapid development in the brain and rapid weight gain. Typically, by the 36th week, the fetus begins descending head-first into the uterine cavity. Getting ready for birth is not the only behavior exhibited during this last trimester. Erectile responses in male fetuses occur during this time (Haffner, 1999; Martinson, 1994; Parrot, 1994); and Giorgi and Siccardi (1996) reported ultrasonographic observations of a fetus performing self-exploration of her external sex organs. Most babies are born vaginally (through the vagina), though in the United States one-third are by Cesarean section (through the abdomen; Molina et al., 2015). A newborn’s health is initially determined by his/her weight (normally ranging between 2,500 and 4,000 grams)—though birth weight significantly differs between ethnicities (Jannsen et al., 2007).

Birth Control

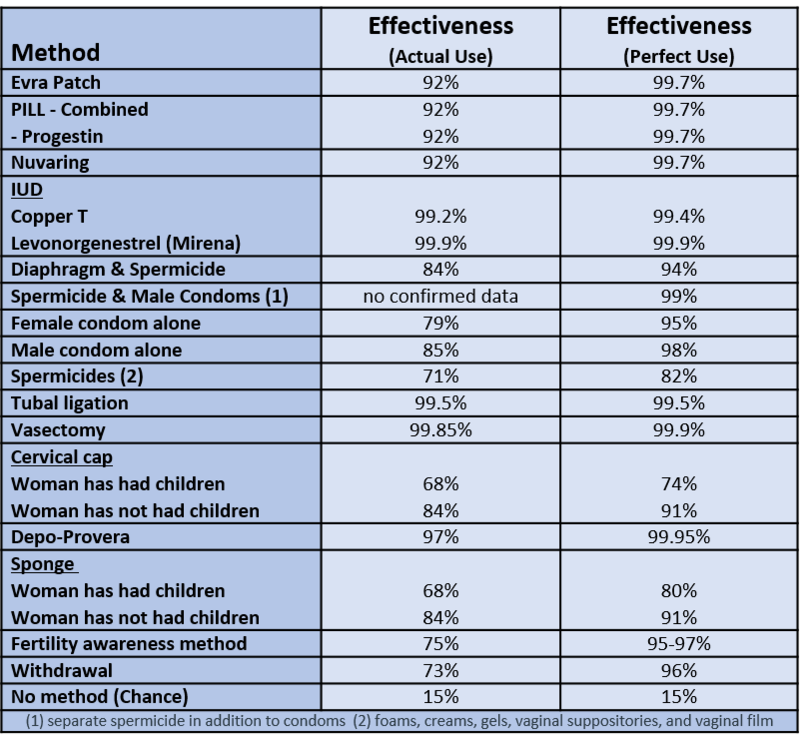

Contraception, or birth control, reduces the probability of pregnancy resulting from sexual intercourse. There are various forms of birth control, including: hormonal, barrier, or natural. As shown in Table 1, the effectiveness of the different forms of birth control ranges widely, from 68% to 99.9% (optionsforsexualhealth.org).

Hormonal forms of birth control release synthetic estrogen or progestin, which prevents ovulation and thickens cervical mucus, making it difficult for sperm to reach ova (sexandu.ca/contraception). There are a variety of ways to introduce these hormones into the body, including: implantable rods, birth control pills, injections, transdermal patches, IUDs, and vaginal rings. For example, the vaginal ring is 92% effective, easily inserted into and taken out of the vagina by the user, and comprised of thin plastic containing a combination of hormones that are released during the time it is in the vagina—usually about three weeks.

Barrier forms of birth control prevent sperm from entering the uterus by creating a physical barrier or chemical barrier toxic to sperm. There are a variety of barrier methods, including: vasectomies, tubal ligations, male and female condoms, spermicides, diaphragms, and cervical caps. The most popular barrier method is the condom, which is 79-85% effective. The male condom is placed over the penis, whereas the female condom is worn inside the vagina and fits around the cervix. Condoms prevent bodily fluids from being exchanged and reduce skin-to-skin contact. For this reason, condoms are also used to reduce the risk of some sexually transmitted infections (STIs). However, it is important to note that male and female condoms, or two male condoms, should not be worn simultaneously during penetration; the friction between multiple condoms creates microscopic tears, rendering them ineffective (Munoz, Davtyan & Brown, 2014).

Natural forms of birth control rely on knowledge of the menstrual cycle and awareness of the body. They include the Fertility Awareness Method (FAM), lactational amenorrhea method, and withdrawal. For example, the FAM is about 75% effective, and requires tracking the menstrual cycle, and avoiding sexual intercourse or using other forms of birth control during the female’s fertile window. About 30% of females’ fertile windows—the period when a female is most likely to conceive—are between days ten and seventeen of their menstrual cycle (Wilcox, Dunson & Baird, 2000). The remaining 70% of females experience irregular and less predictable fertile windows, reducing the efficacy of the FAM.

Other forms of birth control that do not fit into the above categories include: emergency contraceptive pills, the copper IUD, and abstinence. Emergency contraceptive pills (e.g., Plan B) delay the release of an ovum if taken prior to ovulation. Emergency contraception is a form of birth control typically used after unprotected sex, condom mishaps, or sexual assault. The most effective form of emergency contraception is the copper IUD. A medical professional inserts the IUD through the opening of the cervix and into the uterus. It is more than 99% effective and may be left within the uterus for over 10 years. It differs from typical IUDs because it is hormone-free and uses copper ions to create an inhospitable environment for sperm, thus significantly reducing the chances of fertilization. Additionally, the copper ions alter the lining of the uterus, which significantly reduces the probability of implantation. Lastly, abstinence—avoiding any sexual behaviors that may lead to conception—is the only form of birth control with a 100% effective rate.

There are many factors that determine the best birth control options for any particular person. Some factors are related to personality and habits. For example, if a woman is a forgetful person, “the pill” may not be her best option, since it requires being taken daily. Other factors that influence birth control choices include cost, age, education, religious beliefs, lifestyle, and sexual health.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Unfortunately, a potential outcome of sexual activity is infection. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are like other transmittable infections, except STIs are primarily transmitted through social sexual behaviors. Social sexual behaviors include romantic kissing and oral, vaginal, and anal sex. Additionally, STIs can be transmitted through blood, and from mother to child during pregnancy and childbirth. STIs may lead to sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Often, infections have no symptoms and do not lead to diseases. For example, the most common STI for men and women in the US is Human Papillomavirus (HPV). In most cases, HPV goes away on its own and has no symptoms. Only a fraction of HPV STIs develop into cervical, penile, mouth, or throat cancer (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDCP, December 2016).

There are more than 30 different STIs. STIs differ in their primary methods of transmission, symptoms, treatments, and whether they are caused by viruses or bacteria. Worldwide, some of the most common STIs are: genital herpes (500 million), HPV (290 million), trichomoniasis (143 million), chlamydia (131 million), gonorrhoea (78 million), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV, 36 million), and syphilis (6 million; World Health Organization, 2016).

Medical testing to determine whether someone has an STI is relatively simple and often free (gettested.cdc.gov). Further, there are vaccines or treatments for all STIs, and many STIs are curable (e.g., chlamydia, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis). However, without seeking treatment, all STIs have potential negative health effects, including death from some. For example, if untreated, HIV often leads to the STD acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)—over one million people die every year from AIDs (aids.gov). Unfortunately, many, if not most, people with STIs never get tested or treated. For example, as many as 30% of those with HIV and 90% of those with genital herpes are unaware of having an STI (Fleming et al., 1997; Nguyen & Holodniy, 2008).

It is impossible to contract an STI from a person who does not have an STI. This may seem like an obvious statement, but a recent study asked 596 freshmen- and sophomore-level college students the following True/False question, “A person can get AIDS by having anal (rectal) intercourse even if neither partner is infected with the AIDS virus,” and found that 33% of them answered “true” (Lucas et al., 2016). What is obvious, is that false stereotypes about anal sex causing AIDS continue to misinform our collective sexual knowledge. Only open, honest, and comprehensive education about human sexuality can fight these STI stereotypes. To be clear, anal sex is associated with STIs, but it cannot cause an STI. Specifically, anal sex, when compared to vaginal sex (the second most likely method of transmission), oral sex (third most likely), and romantic kissing (fourth most likely), is associated with the greatest risk of transmitting and contracting STIs, because the tissue lining of the rectum is relatively thin and apt to tear and bleed, thereby passing on the infection (CDCP, 2016).

A sexually active person’s chance of getting an STI depends on a variety of factors. Two of these are age and access to sex education. Young people between the ages of 15 and 24 account for more than 50% of all new STIs, even though they account for only about 25% of the sexually active population (Satterwhite et al., 2013). Generally, young males and females are equally susceptible to getting an STI; however, females are much more likely to suffer long-term health consequences of an STI. For example, each year in the US, undiagnosed STDs cause about 24,000 females to become infertile (CDCP, October 2016; DiClemente, Salazar & Crosby, 2007).

Limited access to comprehensive sex education is also a major contributing factor toward the risk of contracting an STI. Unfortunately, some sex education is limited to the promotion of abstinence, and relies heavily on “virginity pledges.” A virginity pledge is a commitment to refrain from sexual intercourse until heterosexual marriage. Although virginity pledges fit well with some cultural and religious worldviews, they are only effective if people, in fact, remain abstinent. Unfortunately, this is not always the case; research reveals many ways these types of strategies can backfire. Adolescents who take virginity pledges are significantly less likely than other adolescents to use contraception when they do become sexually active (Bearman & Brückner, 2001). Further, virginity pledgers are four to six times more likely than non-pledgers to engage in both oral and anal intercourse (Paik, Sanchagrin & Heimer, 2016), often assuming they’re preserving their virgin status by simply avoiding vaginal sex. In fact, schools with students taking virginity pledges have significantly higher rates of STIs than other schools (Bearman & Brückner, 2001).

Interestingly, senior citizens are one of the fastest growing segments of the European and US populations being diagnosed with STIs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report a steady increase in people over 65 being diagnosed with HIV; since 2007, incidence of syphilis among seniors is up by 52% and chlamydia is up by 32%; and from 2010 to 2014, there was a 38% increase in STI diagnoses in people between the ages of 50 and 70 (Forster, 2016; Weiss, 2014). Why is this happening? Bear in mind, seniors are not necessarily more sexually knowledgeable than adolescents; they may have no greater access to comprehensive sex education than younger people (Adams, Oye & Parker, 2003). Even so, medical advances allow seniors to continue to be sexually active at later points in their lifespan—and to make the same mistakes adolescents make about safer sex.

Safer Sex

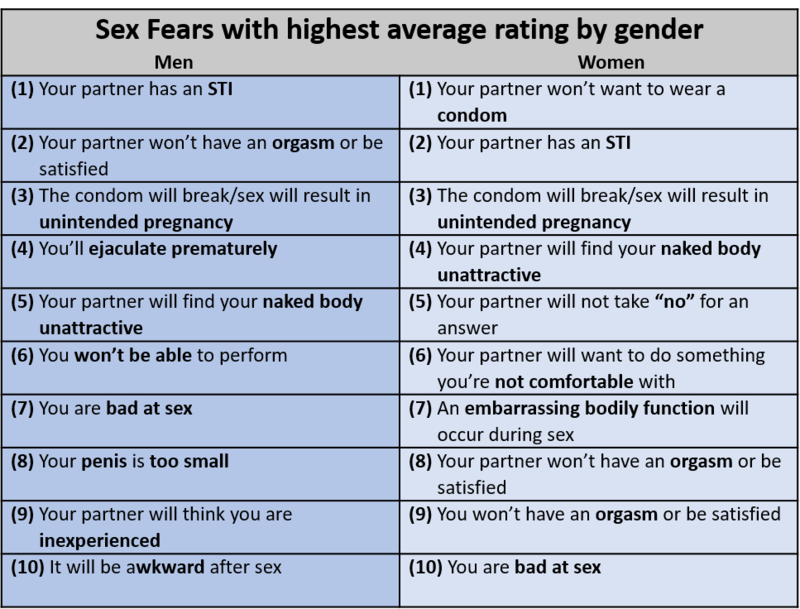

STIs are 100% preventable: Simply don’t engage in social sexual behaviors. But in the grand scheme of things, you may be surprised to hear, avoiding sex is detrimental to your physical and mental well-being—whereas, having sex can be widely beneficial (Charnetski & Brennan, 2004; Ditzen, Hoppmann & Klumb, 2008; Hall et al., 2010). Thus, we recommend safer-sex practices, such as communication, honesty, and barrier methods. Safer-sex practices always begin with communication. Before engaging in sexual behaviors with a partner, a clear, honest, and explicit understanding of your boundaries, as well as your partner’s, should be established. Safer sex involves discussing and using barriers—male condoms, female condoms, or dental dams—relative to your specific sexual behaviors. Also, keep in mind: Although safer sex may use some of the same tools as birth control, safer sex is not birth control. Birth control focuses on reproduction; safer sex focuses on well-being. A proactive approach to behaving sexually may at first seem burdensome, but it can be easily reimagined as “foreplay,” is associated with greater sexual satisfaction, increases the probability of orgasm, and addresses fears people have during sex (see Table 2; Jalili, 2016; Nuno, 2017).

Sexual Dysfunctions

Roughly 43% of women and 31% of men suffer from a clinically significant impairment to their ability to experience sexual pleasure or responsiveness as outlined by the SRC (Rosen, 2000). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM) refers to these difficulties as sexual dysfunctions.

According to the DSM, there are four male-specific dysfunctions:

- delayed ejaculation

- erectile disorder (ED)

- male hypoactive sexual desire disorder

- premature ejaculation (PE)

There are three female-specific dysfunctions:

- female orgasmic disorder

- female sexual interest/arousal disorder

- genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder

There is also one non-gender-specific sexual dysfunction: substance-/medication-induced sexual dysfunction (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The most commonly reported male sexual dysfunctions are premature ejaculation (PE) and erectile dysfunction (ED), whereas females most frequently report dysfunctions involving desire and arousal. Females are also more likely to experience multiple sexual dysfunctions (McCabe et al., 2016).

PE is a pattern of early ejaculation that impairs sexual performance and causes personal distress. In severe cases, ejaculation may occur prior to the start of sexual activity or within 15 seconds of penetration (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). PE is a fairly common sexual dysfunction, with prevalence rates ranging from 20-30%. Relationship and intimacy difficulties, as well as anxiety, low self-confidence, and depression, are often associated with PE. Most males with PE do not seek treatment (Porst et al., 2007).

ED is the frequent difficulty to either obtain or maintain an erection, or a significant decrease in erectile firmness. Normal aging increases the prevalence and incidence rates of erectile difficulties, especially after the age of 50 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). However, recent studies have found significant increases in the prevalence of ED in young men, less than 30 years of age (e.g., Capogrosso et al., 2013).

Female sexual interest/arousal disorder (FSIAD) is characterized by reduced or absent sexual interest or arousal. A person diagnosed with FSIAD has had an absence of at least three of the following emotions, behaviors, and thoughts for more than six months:

- interest in sexual activity

- sexual or erotic thoughts and fantasies

- initiation of sexual activity

- sexual excitement or pleasure during sexual activity

- sexual interest/arousal in response to sexual or erotic cues

- genital or non-genital sensations during sexual activity

FSIAD is not diagnosed if the presenting symptoms are a result of insufficient stimulation or lack of sexual knowledge—such as the erroneous expectation that penile-vaginal intercourse always results in orgasm (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Treatments

When it comes to treating sexual dysfunctions, there’s some good news and there’s some bad news. The good news is that most sexual dysfunctions have treatments—however, most people don’t seek them out (Gott & Hinchliff, 2003). So, the further good news is that—once you have the knowledge (say, from this module)—if you experience such difficulties, getting treatment is just a matter of making the choice to seek it out. Unfortunately, the bad news is that most treatments for sexual dysfunctions don’t address the psychological and sociocultural underpinnings of the problems, but instead focus exclusively on the physiological roots. For example, Montague et al. (2007, pg. 1-7) make this point perfectly clear in The American Urological Association’s treatment options for ED: “The currently available therapies…for the treatment of erectile dysfunction include the following: oral phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, intra-urethral alprostadil, intracavernous vasoactive drug injection, vacuum constriction devices, and penile prosthesis implantation.”

Treatments that focus solely on managing symptoms with biological fixes neglect the fundamental issue of sexual dysfunctions being grounded in psychological, relational, and social contexts. For example, a female seeking treatment for inadequate lubrication during intercourse is most likely to be prescribed a supplemental lubricant to alleviate her symptoms. The next time she is sexually intimate, the lubricant may solve her vaginal dryness, but her lack of natural arousal and lubrication due to partner abuse, is completely overlooked (Kleinplatz, 2012).

There are numerous factors associated with sexual dysfunctions, including: relationship issues; adverse sexual attitudes and beliefs; medical issues; sexually-oppressive cultural attitudes, codes, or laws; and a general lack of knowledge. Thus, treatments for sexual dysfunctions should address the physiological, psychological, and sociocultural roots of the problem.

Conclusion

We hope the information in this module has a positive impact on your physical, psychological, and relational health. As we initially promised, your clandestine Google searches should decrease now that you’ve acquired a scientifically-based foundation in sexual anatomy and physiology. What we neglected to mention earlier is that this foundation may dramatically increase your overt Google searches about sexuality! Exploring human sexuality is a limitless enterprise. And, by embracing your innate curiosity and sexual knowledge, we predict your sexual-literacy journeys are just beginning.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Robert Biswas-Diener, Trina Cowan, Kara Paige, and Liz Wright for editing drafts of this module.

Outside Resources

- Journal: The Journal of Sex Research

- http://www.sexscience.org/journal_of_sex_research/

- Journal: The Journal of Sexual Medicine

- http://www.jsm.jsexmed.org/

- Organization: Advocates for Youth partners with youth leaders, adult allies, and youth-serving organizations to advocate for policies and champion programs that recognize young people’s rights to honest sexual health information; accessible, confidential, and affordable sexual health services; and the resources and opportunities necessary to create sexual health equity for all youth.

- http://www.advocatesforyouth.org/

- Organization: SIECUS - the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States - was founded in 1964 to provide education and information about sexuality and sexual and reproductive health.

- http://www.siecus.org/

- Organization: The Guttmacher Institute is a leading research and policy organization committed to advancing sexual and reproductive health and rights in the United States and globally.

- https://www.guttmacher.org/

- Video: 5MIweekly—YouTube channel with weekly videos that playfully and scientifically examine human sexuality.

- https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQFQ0vPPNPS-LYhlbKOzpFw

- Video: Sexplanations—YouTube channel with shame-free educational videos on everything sex.

- https://www.youtube.com/user/sexplanations

- Video: YouTube - AsapSCIENCE

- https://www.youtube.com/user/AsapSCIENCE

- Web: Kinsey Confidential—Podcast with empirically-based answers about sexual questions.

- http://kinseyconfidential.org/

- Web: Sex & Psychology Web: Sex & Psychology—Blog about the science of sex, love, and relationships.

- http://www.lehmiller.com/

Discussion Questions

- Consider your own source(s) of sexual anatomy and physiology information previous to this module. Discuss at least three of your own prior sexual beliefs challenged by the content of this module.

- Pretend you are tasked with teaching a group of adolescents about sexual anatomy, but with a twist: You must teach through the lens of pleasure instead of reproduction. What would your talking points be? Be sure to incorporate the role of the brain in evoking sexual pleasure.

- Given how universal and similar the sexual response cycle is for both males and females, why do you think males enter a refractory period during the resolution phase and females do not? Consider potential evolutionary reasons for why this occurs.

- Imagine yourself as a developing human being from conception to birth. Using a first-person point of view, create a commentary that addresses the significant milestones achieved in each trimester.

- Pretend your hypothetical adolescent daughter has expressed interest in birth control. During her appointment with a health care provider, what are some factors that should be considered prior to selecting the best birth control method for her?

- Describe at least three ways you can reduce your chances of contracting a sexually transmitted infection.

- How can practicing safer sex enhance your well-being?

- As discussed within the module, numerous influences contribute to the development and maintenance of a sexual dysfunction, such as, adverse sexual attitudes and beliefs. Which influences, if any, can you relate to? How do you plan on addressing those influences to achieve optimal sexual health?

Vocabulary

- Abstinence

- Avoiding any sexual behaviors that may lead to conception.

- Age of viability

- The age at which a fetus can survive outside of the uterus.

- Barrier forms of birth control

- Methods in which sperm is prevented from entering the uterus, either through physical or chemical barriers.

- Cervix

- The lower portion of the uterus that connects to the vagina.

- Chromosomal sex

- Also known as genetic sex; defined by the 23rd set of chromosomes.

- Clitoris

- A sensitive and erectile part of the vulva; its main function is to initiate orgasms.

- Conception

- Occurs typically within the fallopian tube, when a single sperm fertilizes an ovum cell.

- Cowper's glands

- Glands that produce a fluid that lubricates the urethra and neutralizes any acidity due to urine.

- Emergency contraception

- A form of birth control used in a variety of circumstances, such as after unprotected sex, condom mishaps, or sexual assault.

- Epididymis

- A twisted duct that matures, stores, and transports sperm cells into the vas deferens.

- Erogenous zones

- Highly sensitive areas of the body.

- Excitement phase

- The activation of the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system defines this phase of the sexual response cycle; heart rate and breathing accelerate, along with increased blood flow to the penis, vaginal walls, clitoris, and nipples.

- Fallopian tubes

- The female’s internal sex organ where fertilization is most likely to occur.

- Foreskin

- The skin covering the glans or head of the penis.

- Glans penis

- The highly sensitive head of the penis, associated with initiating orgasms.

- Hormonal forms of birth control

- Methods by which synthetic estrogen or progesterone are released to prevent ovulation and thicken cervical mucus.

- Introitus

- The vaginal opening to the outside of the body.

- Labia majora

- The “large lips” enclosing and protecting the female internal sex organs.

- Labia minora

- The “small lips” surrounding and defining the openings of the vagina and urethra.

- Menstruation

- The process by which ova as well as the lining of the uterus are discharged from the vagina after fertilization does not occur.

- Mullerian ducts

- Primitive female internal sex organs.

- Myotonia

- Involuntary muscular movements, such as facial grimaces, that occur during the excitement phase of the sexual response cycle.

- Natural forms of birth control

- Methods that rely on knowledge of the menstrual cycle and awareness of the body.

- Neuroimaging techniques

- Seeing and measuring live and active brains by such techniques as electroencephalography (EEG), computerized axial tomography (CAT), and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

- Orgasm phase

- The shortest, but most pleasurable, phase of the sexual response cycle.

- Orgasmic platform

- The tightening of the outer third of the vaginal walls during the plateau phase of the sexual response cycle.

- Ovaries

- The glands housing the ova and producing progesterone, estrogen, and small amounts of testosterone.

- Ovulation

- When ova travel from the ovaries to the uterus.

- Oxytocin

- A neurotransmitter that regulates bonding and sexual reproduction.

- Penis

- The most prominent external sex organ in males; it has three main functions: initiating orgasm, and transporting semen and urine outside of the body.

- Plateau phase

- The phase of the sexual response cycle in which blood flow, heart rate, and breathing intensify.

- Plethysmography

- The measuring of changes in blood - or airflow - to organs.

- Pregnancy

- The time in which a female carries a developing human within her uterus.

- Primitive gonads

- Reproductive structures in embryos that will eventually develop into ovaries or testes.

- Prostate gland

- A male gland that releases prostatic fluid to nourish sperm cells.

- Quickening

- The feeling of fetal movement.

- Refractory period

- Time following male ejaculation in which he is unresponsive to sexual stimuli.

- Resolution phase

- The phase of the sexual response cycle in which the body returns to a pre-aroused state.

- Safer-sex practices

- Doing anything that may decrease the probability of sexual assault, sexually transmitted infections, or unwanted pregnancy; these may include using condoms, honesty, and communication.

- Scrotum

- The sac of skin behind and below the penis, containing the testicles.

- Semen

- The fluid that sperm cells are transported within.

- Seminal vesicles

- Glands that provide sperm cells the energy that allows them to move.

- Sexual dysfunctions

- A range of clinically significant impairments in a person’s ability to experience pleasure or respond sexually as outlined by the sexual response cycle.

- Sexual response cycle

- Excitement, Plateau, Orgasm, and Resolution.

- Sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

- Infections primarily transmitted through social sexual behaviors.

- Skene’s glands

- Also called minor vestibular glands, these glands are on the anterior wall of the vagina and are associated with female ejaculation.

- Somatosensory cortex

- A portion of the parietal cortex that processes sensory information from the skin.

- Testicles

- Also called testes—the glands producing testosterone, progesterone, small amounts of estrogen, and sperm cells.

- Trimesters

- Phases of gestation, beginning with the last menstrual period and ending about 40 weeks later; each trimester is roughly 13 weeks in length.

- Urethra

- The tube that carries urine and semen outside of the body.

- Uterus

- Also called the womb—the female’s internal sex organ where offspring develop until birth.

- Vagina

- Also called the birth canal—a muscular canal that spans from the cervix to the introitus, it acts as a transport mechanism for sperm cells coming in, and menstrual fluid and babies going out.

- Vas deferens

- A muscular tube that transports mature sperm to the urethra.

- Vasectomy

- A surgical form of birth control in males, in which the vas deferens is intentionally damaged.

- Vestibular glands (VGs)

- Also called major vestibular glands, these glands are located just to the left and right of the vagina, and produce lubrication to aid in sexual intercourse.

- Vulva

- The female’s external sex organs.

- Wolffian ducts

- Primitive male internal sex organs.

- Zygote

- Fertilized ovum.

References

- Adams, M., S., Oye, J., & Parker, T. S. (2003). Sexuality of older adults and the Internet: From sex education to cybersex. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 18, 405-415.

- Aisch, G., & Marsh, B. (2014). How Likely Is It That Birth Control Could Let You Down?https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/09/14/sunday-review/unplanned-pregnancies.html. Retrieved on March 23, 2017.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

- Anderson, M. R., Klink, K., & Cohrssen, A. (2004). Evaluation of vaginal complaints. Journal of The American Medical Association, 291, 1368-1379.

- Bearman, P. S., & Brückner, H. (2001). Promising the future: Virginity pledges and first intercourse. American Journal of Sociology, 106, 859-912.

- Buhi, E.R., Daley, E.M., Oberne, A., Smith, S.A., Schneider, T., Fuhrmann, H.J.(2010). Quality and accuracy of sexual health information web sites visited by young people. Journal of Adolescent Health, Volume 47, Issue 2 , 206 - 208.

- Capogrosso, P., Colicchia, M., Ventimiglia, E., Castagna, G., Clementi, M. C., Suardi, N., Castiglione, F., Briganti, A., Cantiello, F., Damiano, R., Montorsi, F., & Salonia, A. (2013). One patient out of four with newly diagnosed erectile dysfunction is a young man—worrisome picture from the everyday clinical practice. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10, 1833-1841.

- Carlson, N. R. (1986). Physiology of behavior. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016). Anal sex and HIV risk. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/analsex.html Retrieved on March 21, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (December 2016). What is HPV? https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/whatishpv.html Retrieved on May 6, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (October 2016). Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats15/std-surveillance-2015-print.pdf Retrieved on May 6, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control, National HIV, STD, and Hepatitis Testing.

- Charnetski, C. J., & Brennan, F. X. (2004). Sexual frequency and salivary Immunoglobulin A (IgA). Psychological Reports, 94, 839-844.

- DiClemente, R. J., Salazar, L. F., & Crosby, R. A. (2007). A review of STD/HIV preventive interventions for adolescents: Sustaining effects using an ecological approach. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32, 888-906.

- Diedrich, K., Fauser, B. C. J. M., Devroey, P., & Griesinger, G. (2007). The role of the endometrium and embryo in human implantation. Human Reproduction Update, 13, 365-377.

- Ditzen, B., Hoppmann, C., & Klumb, P. (2008). Positive couple interactions and daily cortisol: On the stress-protecting role of intimacy. Psychosomatic Medicine, 70, 883-889.

- Dreger, A. (1998). Ambiguous sex—or ambivalent medicine? Ethical issues in the treatment of intersexuality. Hastings Center Report, 28, 24-35.

- Faddy, M.J., Gosden, R. G., Gougeon, A., Richardson, S. J., & Nelson, J. F. (1992). Accelerated disappearance of ovarian follicles in mid-life: Implications for forecasting menopause. Human Reproduction, 7, 1342–1346.

- Fadul, C. E., Stommel, E. W., Dragnev, K. H., Eskey, C. J., & Dalmau, J. O. (2005). Focal paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis presenting as orgasmic epilepsy. Journal of Neuro Oncology, 72, 195–198.

- Fleming, D. T., et al. (1997). Herpes simplex virus type 2 in the United States, 1976–1994. New England Journal of Medicine, 337, 1105–1111.

- Forster, K. (December 8, 2016). STIs in people aged 50 to 70 have risen by more than a third over the last decade. Independent. http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/health-news/older-people-stis-sexually-transmitted-infections-50-to-70-chief-medical-officer-report-dame-sally-a7463861.html Retrieved on May 9, 2017.

- Fuxman, S., De Los Santos, S., Finkelstein, D., Landon, M. K., & O’Donnell, L. (2015). Sources of information on sex and antecedents of early sexual initiation among urban Latino youth. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 10, 333-350.

- Ginger, V. A. T., & Yang, C. C. (2011). Functional anatomy of the female sex organs. In Mulhall, J. P., Incrocci, L., Goldstein, I., & Rosen, R. (eds). Cancer and sexual health. Springer Publishing.

- Giorgi, G., & Siccardi, M. (1996). Ultrasonographic observation of a female fetus sexual behavior in utero [Letter to the editors]. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 175,(3, Part 1).

- Google Search Statistics, http://www.internetlivestats.com/google-search-statistics/ Retrieved on May 5, 2017.

- Gott, M., & Hinchliff, S. (2003). Barriers to seeking treatment for sexual problems in primary care: A qualitative study with older people. Family Practice, 20, 690-695.

- Grumbach, M. M., & Conte, F. A. (1998). Disorders of sex differentiation. In: Wilson, J. D., Foster, D. W., Kronenborg, H. M., & Larsen, P. R. (Eds.) Williams Textbook of Endocrinology, Ed:9th. (pps. 1303-1425). Philadelphia: WB Saunders.

- Haffner, D. W. (1999). From diapers to dating: A parent\'s guide to raising sexually healthy children. New York, NY: Newmarket Press.

- Halata, Z., & Spaethe, A. (1997). Sensory innervation of the human penis. Advanced Experimental Medical Biology, 424, 265–266.

- Hall, S. A., Shackelton, R., Rosen, R. C., & Araujo, A. B. (2010). Sexual activity, erectile dysfunction, and incident cardiovascular events. American Journal of Cardiology, 105, 192-197.

- Herdt, G. (1996). Third sex, third gender–Beyond sexual dimorphism in culture and history. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Hines, T. (2001). The G-Spot: A modern gynecologic myth. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 185, 359–362.

- Igbinedion, B. O. E., & Akhigbe, T. O. (2012). The accuracy of 2D ultrasound prenatal sex determination. Nigerian Medical Journal: Journal of the Nigeria Medical Association, 53, 71–75.

- Jalili, C. (2016). Here’s what 2,000 men and women fear the most about sex. Elite Daily. http://elitedaily.com/dating/fears-sex-study/ Retrieved on May 10, 2017.

- Jannini, E. A., Rubio‐Casillas, A., Whipple, B., Buisson, O., Komisaruk, B. R., & Brody, S. (2012). Female orgasm(s): One, two, several. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9, 956–965.

- Janssen, P. A., Thiessen, P., Klein, M. C., Whitfield, M. F., MacNab, Y. C., & Cullis-Kuhl, S. C. (2007). Standards for the measurement of birth weight, length and head circumference at term in neonates of European, Chinese and South Asian ancestry. Open Medicine, 1, e74–e88.

- Kilchevsky, A., Vardi, Y., Lowenstein, L., & Gruenwald, I. (2012). Is the female G-Spot truly a distinct anatomic entity? Sexual Medicine, 9, 719-726.

- Killick, S. R., Leary, C., Trussell, J., & Guthrie, K. A. (2011). Sperm content of pre-ejaculatory fluid. Human Fertility, 14, 48-52.

- King, B. M. (2015). Human Sexuality Today (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Kleinplatz, P. J. (2012). New directions in sex therapy: Innovations and alternatives. New York: Routledge.

- Komisaruk, B. R., Wise, N., Frangos, E., Liu, W., Allen, K., & Brody, S. (2011). Women\'s clitoris, vagina and cervix mapped on the sensory cortex: fMRI evidence. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10, 822–830.

- Lucas, D. R., & Fox, J. (2018). The psychology of human sexuality. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. DOI:nobaproject.com).

- Lucas, D. R., Roberts, C., Nylander, G., & Higdon, M. (2016). Do Americans know more about sex today than they did 25 years ago? Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Southwestern Psychological Association, Dallas, Texas.

- Martinson, F. M. (1994). The sexual life of children. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

- Masters, W. H., & Johnson, V. E. (1966). Human Sexual Response. Boston: Little, Brown.

- McCabe, M.P., Sharlip, I.D., Lewis, R., Atalla, E., Balon, R., Fisher, A.D., Laumann, E., Lee, S.W., & Segraves, R.T. (2016). Incidence and prevalence of sexual dysfunction in women and men: A consensus statement from the fourth international consultation on sexual medicine 2015. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13, 144 -152.

- Molina G., Weiser, T.G., Lipsitz, S. R., Esquivel, M. M., Uribe-Leitz, T., Azad, T., Shah, N., Semrau, K., Berry, W. R., Gawande, A. A., & Haynes, A. B. Relationship between Cesarean delivery rate and maternal and neonatal mortality. Journal of the American Medical Association, 314, 2263-2270.

- Montague, D. K., Jarow, J. P., Broderick, G. A., et al. (2007). The management of erectile dysfunction: An update. The American Urological Association. Journal of Urology, June.

- Moore, K.T., Persaud, T.V.N., & Torchia, M.G. (2016). The developing human: Clinically oriented embryology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc.

- Munoz, K., Davtyan, M., & Brown, B. (2014). Revisiting the condom riddle: Solutions and implications. Electronic Journal of Human Sexuality, 17.

- Nappi, R. E., & Lachowsky, M. (2009). Menopause and sexuality: Prevalence of symptoms and impact on quality of life. Maturitas, 63, 138-141.

- Nguyen, N., & Holodniy, M. (2008). HIV infection in the elderly. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 3, 453–472.

- Nummenmaa, L., Suvilehto, J.T., Glerean, E., Santtila, P., & Hietanen, J. K. (2016). Topography of human erogenous zones. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45, 1207-1216.

- Nuno, S. M. (2017). Let's talk about sex: The importance of open communication about sexuality before and during Relationships. In N. R. Stilton (Ed.), Family Dynamics and Romantic Relationships in a Changing Society (pp. 47-61). IGI Global.

- O'Connell, H.E., Sanjeevan, K.V., & Hutson, J. M. (2005). Anatomy of the clitoris. Journal of Urology, 174, 1189-1195.

- Odeh M., Ophir E., & Bornstein J. (2008). Hypospadias mimicking female genitalia on early second trimester sonographic examination. Journal of Clinical Ultrasound, 36, 581–583.

- Opperman, E., Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Rogers, C. (2014). It feels so good it almost hurts: Young adults experiences of orgasm and sexual pleasure. The Journal of Sex Research, 51, 503-515.

- Options for Sexual Health. Retrieved on July 2, 2017.

- Ortigue, S., Grafton, S. T., & Bianchi-Demicheli, F. (2007). Correlation between insula activation and self-reported quality of orgasm in women. Neuroimage, 37, 551-560.

- Owen, D. H., & Katz, D. F. (2005). A review of the physical and chemical properties of human semen and the formulation of a semen simulant. Journal of Andrology, 26, 459–469.

- Paik, A., Sanchagrin, K. J., & Heimer, K. (2016). Broken promises: Abstinence pledging and sexual and reproductive health. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 546-561.

- Parrot, A. (1994). Incest, infertility, infant sexuality. In Bullough, V. & Bullough, B. (Eds.), Human Sexuality Encyclopedia (pp. 289-310). New York, NY: Garland.

- Penfield, W., & Boldrey, E. (1937). Somatic motor and sensory representation in the cerebral cortex of man as studied by electrical stimulation. Brain, 60, 389-443.

- Porst, H., Montorsi, F., Rosen, R.C., Gaynor, L., Grupe, S., & Alexander, J. (2007). The Premature Ejaculation Prevalence and Attitudes (PEPA) survey: Prevalence, comorbidities, and professional help-seeking. European Urology, 51, 816–824.

- Rosen, R. C. (2000). Prevalence and risk factors of sexual dysfunction in men and women. Current Psychiatry Reports, 3,189-195.

- Rysavy, M. A., Li, L., Bell, E. F., Das, A., Hintz, S. R., Stoll, B. J., et al. (2015). Between-hospital variation in treatment and outcomes in extremely preterm infants. New England Journal of Medicine, 372, 1801–1811.

- Satterwhite, C. L., Torrone, E., Meites, E., Dunne, E. F., Mahajan, R., Ocfemia, M. C., Su, J., Xu, F., & Weinstock, H. (2013). Sexually transmitted infections among U.S. women and men: Prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 40, 187-193.

- Shah, J., & Christopher, N. (2002). Can shoe size predict penile length? British Journal of Urology International, 90, 586–587.

- Siminoski, K., & Bain, J. (1993). The relationships among height, penile length, and foot size. Annals of Sex Research, 6, 231-235.

- Simon, L., & Daneback, K. (2013). Adolescents’ use of the Internet for sex education: A thematic and critical review of the literature. International Journal of Sexual Health, 25, 305-319.

- Stephens-Davidowitz, S. (2015). Searching for sex. Sunday Review, New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/25/opinion/sunday/seth-stephens-davidowitz-searching-for-sex.html. Retrieved on May 5, 2017.

- Swaab, D. F. (2004). Sexual differentiation of the human brain: Relevance for gender identity, transsexualism and sexual orientation. Gynecological Endocrinology, 19, 301-312.

- Tachedjiana, G., Aldunatea, M., Bradshawe, C. S., & Coneg, R. A. (in press). The role of lactic acid production by probiotic Lactobacillus species in vaginal health. Research in Microbiology

- The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. Retrieved on July 2, 2017.

- Thompson, D. (2016). Anatomy may be key to female orgasm. https://consumer.healthday.com/sexual-health-information-32/orgasm-health-news-510/anatomy-may-be-key-to-female-orgasm-709934.html. Retrieved on March 25, 2017.

- Veale, D., Miles, S., Bramley, S., Muir, G. & Hodsoll, J. (2015). Am I normal? A systematic review and construction of nomograms for flaccid and erect penis length and circumference in up to 15,521 men. British Journal of Urology International, 115, 978–986.

- Weiss, R. (2014). Baby Boomers Gone Wild! Seniors and STDs. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/love-and-sex-in-the-digital-age/201403/baby-boomers-gone-wild-seniors-and-stds Retrieved on May 6, 2017.

- Wessells, H., Lue, T.F., & McAninch, J. W. (1996). Penile length in the flaccid and erect states: Guidelines for penile augmentation. Journal of Urology, 156, 995-997.

- Wickman, D. (2017). Plasticity of the Skene\'s gland in women who report fluid ejaculation with orgasm. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 14, S67.

- Wilcox, A. J., Dunson, D., & Baird, D. D. (2000). The timing of the “fertile window” in the menstrual cycle: Day specific estimates from a prospective study. British Medical Journal, 321, 1259-1262.

- Wisniewski, A. B., Migeon, C J., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F., Gearhart, J. P., Berkovitz, G. D., Brown, T. R., & Money, J. (2000). Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome: Long-term medical, surgical, and psychosexual outcome. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 85, 2664–2669.

- Wizemann , T. M., & Pardue, M. L. (2001). Sex begins in the womb. In T. M. Wizemann & M. L. Pardue (Eds.), Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health: Does Sex Matter? Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US).

- World Health Organization (August 2016). Sexually transmitted infections (STIs). http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs110/en/ Retrieved May 6, 2017.

Authors

Don LucasDr. Don Lucas is a Professor of Psychology and Coordinator of the Psychology Department at Northwest Vista College in San Antonio, Texas. His teaching over the past three decades has earned him a number of accolades, including the Minnie Stevens Piper Professor Award. He is the author of Being: Your Happiness, Pleasure, and Contentment.

Don LucasDr. Don Lucas is a Professor of Psychology and Coordinator of the Psychology Department at Northwest Vista College in San Antonio, Texas. His teaching over the past three decades has earned him a number of accolades, including the Minnie Stevens Piper Professor Award. He is the author of Being: Your Happiness, Pleasure, and Contentment. Jennifer FoxJennifer Fox is an Assistant Professor of Psychology and Advisor of Psi Beta at Northwest Vista College in San Antonio, Texas. As a Human Sexuality Educator and a mother of a spirited 6-year-old daughter, she is passionate about promoting sexual literacy for all ages.

Jennifer FoxJennifer Fox is an Assistant Professor of Psychology and Advisor of Psi Beta at Northwest Vista College in San Antonio, Texas. As a Human Sexuality Educator and a mother of a spirited 6-year-old daughter, she is passionate about promoting sexual literacy for all ages.

Creative Commons License

Human Sexual Anatomy and Physiology by Don Lucas and Jennifer Fox is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

Human Sexual Anatomy and Physiology by Don Lucas and Jennifer Fox is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.